The Water Quality Assurance Fund is a financial tool to support outsourcing of testing. Ranjiv Khush and Caroline Delaire provide an update on work in Ghana and Kenya.

Safe drinking water is essential for human welfare and progress. This is well understood by government officials in lower-income countries and their development partners. Yet, waterborne diseases remain a leading cause of disease and death, particularly among children, in these settings. Why is progress towards better water safety slow? Experts in water safety management will probably point to the following reasons:

- Water supply managers have limited water quality data.

- Water quality laboratories and trained personnel are expensive.

- Supply chains for water quality diagnostics and reagents are limited.

- Water testing regulations are poorly enforced.

- Water supply managers do not always understand treatment methods.

Are there new ways of approaching water safety management that can address these concerns and accelerate progress towards safe water for all? One strategy is to identify and mitigate risks to water safety before problems arise. Optimally, these proactive risk management approaches, which comprise sanitary surveys and Water Safety Plans, include attention to appropriate treatment methods and verification through regular water quality monitoring. (To learn more about water supply risk management in low-resource settings, please see the World Health Organization’s Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Small Water Supplies.)

Developing a financial innovation for water safety

A more recent innovation for water safety management is the Water Quality Assurance Fund. This was developed by The Aquaya Institute (Aquaya) as a financial tool to support the outsourcing of water quality testing by small suppliers that struggle to maintain on-site testing facilities. At its most basic, the Assurance Fund reduces the risks of non-payment that limit the willingness of professional laboratories to provide testing services to rural water systems. Where the professional laboratory is affiliated with a large urban water supplier, the Assurance Fund can promote greater collaboration between the urban and rural water sectors to understand and manage water safety risks. Finally, it provides a mechanism for channelling subsidies that can defray water testing costs for suppliers coping with revenue shortfalls.

“The Assurance Fund is capitalised with sufficient funds to cover the testing costs of enrolled water systems”

The Assurance Fund is capitalised with sufficient funds to cover the testing costs of enrolled water systems for a predetermined period. Participation terms are negotiated through agreements between the Assurance Fund host organisation (currently Aquaya), regulatory authorities, water suppliers, and testing laboratories. These terms follow the following framework, which is depicted in Figure 1:

- A testing fee is determined between the laboratory and participating water suppliers based on testing schedules, parameters of interest, and water sampling costs.

- If water suppliers fail to pay for testing services within a pre-specified time, the laboratory can file a reimbursement claim for the unpaid testing bill with the Assurance Fund.

- The delinquent water suppliers are then required to reimburse the Assurance Fund for the testing fees, plus a penalty charge.

- In instances of multiple non-payments, the host organisation can withdraw the delinquent water systems from the testing programme.

- In cases where a water system does not have sufficient revenues to support testing costs, and based upon agreed terms, the Assurance Fund can also provide direct payments to the laboratory as a mechanism for subsidising the water system costs.

- The programme should also include technical support for water system operators to interpret water quality test results, develop appropriate treatment responses, and communicate water safety improvements to customers.

For further guidance, please review the Implementation Manual: Water Quality Assurance Fund.

Piloting the Assurance Fund in rural Ghana

With support from the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, Aquaya first tested the Assurance Fund model in Ghana’s Asutifi North district, which is located in the Ahafo region in the centre-west area of the country. Professional laboratory services were provided by a regional laboratory belonging to Ghana Water Company Limited (GWL), the national urban water supplier. The Assurance Fund agreement also included the district government, which owns and oversees local water supply infrastructure, and nine water systems (four piped networks, four handpumps, and one system with two mechanised boreholes that supplied standpipes) that, together, served approximately 30,000 individuals or 60% of the district’s population. The selected water quality parameters included the faecal contamination indicator Escherichia coli (E. coli), and physical parameters, including chlorine, pH, conductivity, total dissolved solids, turbidity, colour, and temperature.

The testing protocol for piped systems corresponded with the sampling frequencies specified by Ghana Standards Authority (GSA): one sample per month for every 5000 individuals served. The monthly sampling frequency exceeded the GSA requirements for handpumps and mechanised boreholes, which only specify biannual sampling of non-piped supplies. However, all parties agreed to the monthly frequency to better monitor faecal contamination of these supplies. To address the higher financial burden that more frequent testing placed upon non-piped systems, the testing costs charged to handpumps and mechanised borehole operators were reduced to the amounts that corresponded with biannual testing. The Assurance Fund directly reimbursed laboratories for the balance.

Between March 2020 and January 2021, the GWL laboratory collected and tested monthly water samples from the nine systems. The results of this exercise included the following findings, which are further discussed in the study brief:

- More than half of the water samples tested positive for E. coli. This evidence of faecal contamination motivated suppliers to improve their chlorination procedures.

- In two-thirds of cases, water systems paid GWL within one-month of receiving test results. In managing delinquencies, GWL preferred to negotiate late payments with suppliers before lodging claims with the Assurance Fund.

- Regular meetings between Aquaya staff and operators from participating water systems promoted better understanding of test results and treatment options.

- Outsourcing testing activities was a cost-effective alternative to establishing and maintaining on-site testing facilities for each water system.

Evaluating the Assurance Fund in Ghana and Kenya

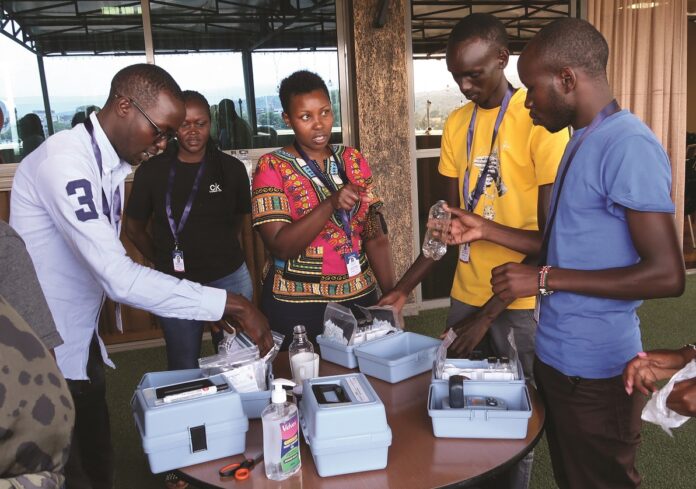

Based on the encouraging pilot results in Asutifi North, larger-scale Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) of the Assurance Fund are now under way in Ghana and Kenya. In Ghana, the RCT is taking place with water systems distributed across 11 districts in the adjacent Ahafo and Bono regions. Testing services are provided by the regional GWL laboratory that participated in the Assurance Fund pilot. In Kenya, the participating water systems are located in Kericho, Nakuru, and Uasin Gishu counties. In each county, testing services are provided by an urban water supplier.

“Evidence of faecal contamination motivated suppliers to improve their chlorination procedures”

These trials are supported by the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID’s) Rural Evidence and Learning for Water (REAL-Water) programme, with co-funding from the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation and The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. REAL-Water is being implemented through a five-year (2021-2026) Cooperative Agreement between USAID and Aquaya.

The Assurance Fund trials are designed to evaluate the programme’s impacts on drinking water quality, commitment to water treatment among system operators, and consumer awareness of water quality issues. The analysis will include calculations of programme implementation costs. The data collection also includes monitoring of payment levels by water systems to ensure good understanding of the prevalence and frequency of subsidy demands in the study regions and the corresponding financial inputs needed to maintain the Assurance Fund.

In both countries, the trials are following a ‘stepped-wedge’ design that proceeds along the following phases: 1) approximately 30 water systems are randomly placed into three different groups; 2) after baseline data collection that covers pre-specified programme indicators, communities in one of the groups receive the Assurance Fund intervention and communities in the remaining two groups serve as controls; 3) every six months mid-line data collection takes place in the intervention and control communities and, subsequently, a control group transitions into an intervention group; 4) after two six-month cycles, all groups will receive the Assurance Fund intervention. Comparisons of indicator measurements between intervention and control communities will provide estimates of the programme impacts.

Though the RCTs are still under way, midline data collection indicates encouraging results. Water operators from systems that are in the Assurance Fund intervention groups report that they are improving water treatment protocols, particularly chlorination, in response to regular receipt of water quality information from the laboratories. Increased engagement between operators and community members is promoting greater public awareness of safe water management. This awareness seems to be increasing demand for water from the participating systems, which may lead to stronger financial positions. In addition, local stakeholders report that, because of concerns over losing customers to systems enrolled in the Assurance Fund, informal water suppliers are registering with local authorities in the hope of becoming eligible for future iterations of the programme.

A call for feedback

As we wait for the final evaluation results, we are gathering ideas and suggestions that will help shape the future of the Assurance Fund, including options for expanding the programme in Ghana and Kenya, and for introducing similar risk-mitigation products that support the outsourcing of water quality testing by small water suppliers in other countries. Even with positive trial outcomes, it is clear that, to scale across additional countries, the Assurance Fund model will have to adapt to relevant institutional frameworks and local economies. Perspectives on the current model, the evaluation, and broader considerations would be greatly appreciated. •

More information

- Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality: Small Water Supplies, WHO. www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240088740

- Implementation Manual: Water Quality Assurance Fund. www.globalwaters.org/resources/assets/implementation-manual-water-quality-assurance-fund

- Conrad N. Hilton Foundation. www.hiltonfoundation.org/

- Asutifi North pilot study brief.

- aquaya.org/wp-content/uploads/2021_Water-Quality-Assurance-Fund-Lessons-Learned-_ResearchBrief.pdf

- REAL-Water programme. www.globalwaters.org/real-water

- The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. helmsleytrust.org/

- Ghana and Kenya project update video. www.youtube.com/watch?v=E4uR7l3ESYU

The authors: Ranjiv Khush (ranjiv@aquaya.org) is co-founder and Caroline Delaire (caroline@aquaya.org) is director of research and programs at The Aquaya Institute. If you are interested in progress with the Assurance Fund and in opportunities to test the approach in other regions, please reach out

Figure 1: A schematic illustration of the Water Quality Assurance Fund.

The Assurance Fund enables small water suppliers that cannot maintain on-site testing facilities to outsource water quality testing to professional laboratories. By guaranteeing that laboratories will be reimbursed in the case of non-payment, the Assurance Fund reduces the risk that laboratories face when providing services to small and rural systems. The programme agreements include requirements for the delinquent water systems to repay the Assurance Fund with penalty fees. The agreements also include the provision of technical support to water system operators to ensure proper interpretations of water quality test results.