Paula Cecilia Soto Ríos and Paola Andrea Alvizuri Tintaya describe Bolivia’s pathway to water resilience in the face of climate change and its impact on the region’s glaciers.

Bolivia holds a unique position in South America’s hydrological landscape, with ecosystems ranging from high-altitude glaciers to Amazonian wetlands. This diversity offers significant opportunities for building a resilient water future. While the country faces pressures from climate variability, demographic change and resource intensive economic activities, it also benefits from a wealth of local knowledge, abundant natural assets, and innovative practices that can strengthen water security for future generations.

In the Andes of Bolivia, high-altitude glaciers supply a substantial share of dry season water to La Paz and El Alto. However, according to studies, these glaciers have experienced a 43% surface area loss since the 1980s. Urban expansion, the growth of industrial and mining activities, and persistent infrastructure challenges have intensified competition for water resources. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC), without adaptation measures, the La Paz-El Alto metropolitan area could experience a 30-40% seasonal water reduction by 2030.

Despite these concerns, Bolivia’s policy frameworks, such as the constitutional recognition of water as a human right, combined with a growing network of community-led water initiatives, provide a strong foundation for adaptive action. A coordinated strategy that blends regulatory enforcement, climate adaptation, technological innovation, and the revitalisation of community-based systems offers a clear pathway to ensuring equitable, reliable and sustainable water access.

Access, gaps and equity

Over the past two decades, Bolivia has made significant progress in extending access to safe drinking water in urban areas. As of 2024, nationwide coverage reached 88% for drinking water and 65.1% for basic sanitation. In urban areas, drinking water coverage stands at 95.5%, compared with 69.7% in rural areas. For basic sanitation, coverage is 72.7% in urban zones, but still only 46.3% in rural areas.

Although the gap between urban and rural access has narrowed, notable disparities remain, especially in sanitation. A 2023 diagnostic by the Ministry of Environment and Water (MMAyA) and the Authority for Oversight and Social Control of Drinking Water and Basic Sanitation (AAPS) identified three critical areas for improvement:

- Coverage and treatment capacity of wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs)

- Operational status and maintenance of these facilities

- Performance of water and sanitation service providers (EPSA).

Addressing these structural challenges alongside climate adaptation measures will be essential for safeguarding Bolivia’s water security in the decades ahead.

Integrating climate adaptation into risk management

Bolivia has strengthened its disaster risk management framework by integrating climate change adaptation into legislative instruments that establish the foundation for preventive and adaptive policies. This includes the Framework Law on Autonomies, the Agricultural Revolution Law, the Risk Management Law, the Mother Earth Law, and the State Planning System. At the regional level, strategic and territorial plans need to incorporate updated risk considerations.

Bolivia’s National Basin Plan (Plan Nacional de Cuencas, PNC), introduced in 2006 and updated for the 2013-17 multi-annual cycle, functions as a flexible, participatory policy, rooted in Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) principles. It emphasises strategic basin governance, intersectoral coordination, and adaptive learning through cyclical planning, allowing the evaluation of past outcomes to inform future policy refinements. Research demonstrates that the PNC represents a deliberate shift away from narrow, infrastructure-focused interventions towards broader social, environmental and institutional integration, reflecting the evolution of Bolivia’s water governance beyond purely remedial measures.

Despite institutional advances, the Katari Basin continues to experience severe environmental stress driven by heavy metal contamination from historic mining, untreated urban wastewater from El Alto, land fragmentation, fragile soils, and increasingly frequent extreme weather events. Academic research shows that acid mine drainage introduces arsenic, cadmium and lead into rivers, while insufficient wastewater treatment has contributed to eutrophication, microbial contamination, and the spread of antibiotic-resistant genes in surface waters. These combined pressures have degraded agricultural soils and reduced crop yields, frequently forcing local authorities to focus on emergency responses rather than sustained, long-term prevention.

The climate clock and opportunities for adaptation

Glaciers are vital freshwater reservoirs, feeding rivers and aquifers, especially during dry seasons, and sustaining both human and ecological systems. In Bolivia, the Andes act as natural water towers, storing precipitation as snow and ice. However, significant glacier loss has been documented because of global warming. Studies indicate that tropical glaciers in the Bolivian Andes have lost approximately half of their volume and surface area since 1975. Growing investment in monitoring, early warning systems, improved reservoir management, and ecosystem restoration in glacier-fed catchments is expected to sustain dry-season flows and support long-term water security.

The World Glacier Monitoring Service reports retreat rates of 0.6-1.2 m of ice thickness per year for glaciers such as Zongo and Illimani. Research has shown that glacier retreat in the Cordillera Real, particularly on peaks such as Huayna Potosí, is exposing new rock outcrops and glacial materials, indicating changes in the hydrological regime. Additionally, the formation of small- and medium-sized lakes at the end of retreating glaciers poses potential risks to downstream communities. These lakes are often unstable and can suddenly release large volumes of water in what are called glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), which can destroy homes, roads, farmland and natural habitats.

By combining scientific monitoring with the participation of local water committees, Bolivia can better anticipate seasonal shortages and optimise water distribution. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), improved irrigation efficiency and crop diversification in rural areas are already helping farmers adapt, reducing projected yield declines of up to 20% by 2050. Combined efforts are crucial for adapting to the challenges posed by glacier retreat and ensuring the resilience of water resources in the region.

Science, communities and cross-border cooperation

Bolivia’s approach to water governance incorporates principles of the United Nations’ (UN) IWRM framework, promoting the sustainable and equitable management of water resources. The UN’s water strategy underscores the importance of cross-sectoral collaboration to address climate change, pollution and biodiversity loss, aligning with Bolivia’s national priorities and global commitments, such as the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

MMAyA is developing specific strategies to implement IWRM policies, with an emphasis on institutional capacity building and technical exchanges within a comprehensive approach to integrated water management. The European Union (EU) supports programmes that provide services in urban, peri-urban, and rural areas, promoting environmental sustainability through IWRM and the realisation of the human right to water and sanitation.

At the local level, Bolivia has implemented the ‘Basin’ model, which is a reciprocal watershed agreement that enables downstream water users to engage with upstream forest owners and landowners to manage their watershed more sustainably. These agreements are funded by water users and local governments, ensuring sustainability without relying on external sources of funding.

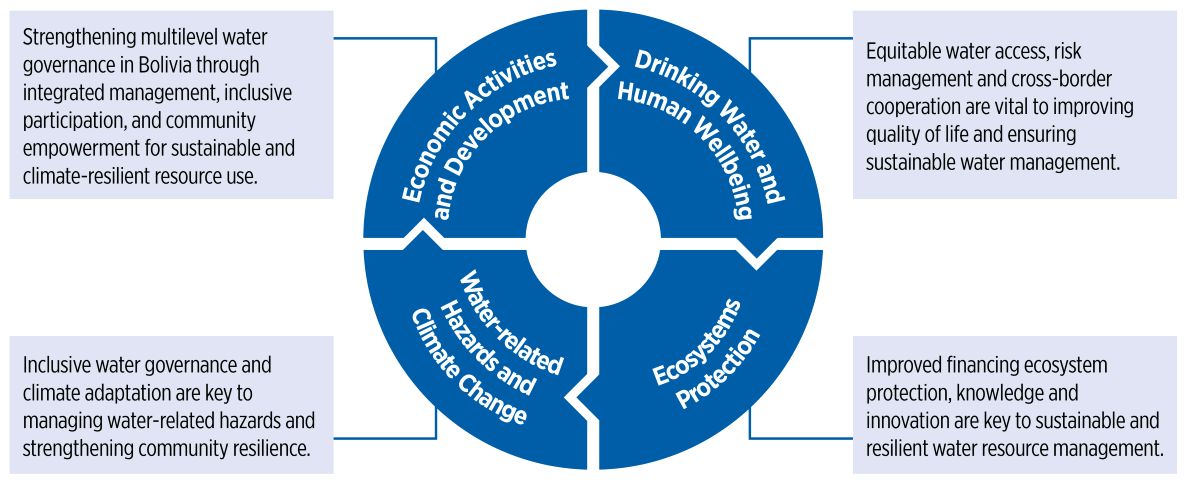

As Figure 1 shows, Bolivia is working towards strengthening climate resilience through projects such as the Enhancing Climate Resilience and Protecting Agricultural Productivity initiative, which focuses on recovering water recharge areas in critical climate-vulnerable zones to safeguard water availability and agricultural productivity. These efforts are advancing in line with the UN’s IWRM framework by gradually integrating national policies, local actions and community participation. However, further work is still needed to fully address the challenges posed by climate change and to ensure long-term water security for all.

As Figure 1 shows, Bolivia is working towards strengthening climate resilience through projects such as the Enhancing Climate Resilience and Protecting Agricultural Productivity initiative, which focuses on recovering water recharge areas in critical climate-vulnerable zones to safeguard water availability and agricultural productivity. These efforts are advancing in line with the UN’s IWRM framework by gradually integrating national policies, local actions and community participation. However, further work is still needed to fully address the challenges posed by climate change and to ensure long-term water security for all.

As for transboundary cooperation, this also plays a vital role, as communities must work together to protect water quality along its entire path from glacier-fed streams to underground aquifers. Achieving this requires inclusive water governance that embraces local knowledge and strengthens social cohesion amid environmental stress.

Another important step is the protection of ecosystems. This is fundamental to ensure the long-term sustainability of water resources, by expanding scientific understanding of the water cycle, improving monitoring systems, and conserving strategic ecosystems that regulate climate and serve as natural water sources. Efforts to restore degraded areas, such as basin headwaters and riverbanks, must go hand in hand with promoting sustainable agricultural practices.

Financing is also critical. Innovative projects are being supported by private sector investment and academic research, pushing forward technology and community-based solutions. In the face of climate change, adaptive action is not just a technical necessity, but also an opportunity to build a more resilient, just and inclusive future for all of Bolivia’s communities.

Towards coordinated action

Bolivia is at a crucial point in managing its water resources facing the challenges driven by climate change, rapid urban expansion and persistent environmental degradation, which threaten the country’s water security, challenging the resilience of both natural systems and human communities. Resilience to these challenges will require institutional and legal assets, including an updated comprehensive regulatory agenda, established administrative capacities and long-standing community-based water management practices, which together constitute a basis for adaptive water governance.

As Bolivia holds a legal framework recognising water as a human right, institutional structures for integrated basin management and long-standing community-based water management practices, these could help advance adaptive and inclusive water management. However, effective progress requires moving beyond policy formulation towards implementation, supported by strengthened inter-institutional coordination, sustained political commitment, and strategic investments capable of delivering measurable and lasting outcomes. To achieve this, integrating climate adaptation into water governance must become a cross-cutting national priority rather than a sectoral concern, ensuring that climate risks are systematically considered in all planning and operational decisions. Partnerships among government, local communities, research institutions, and the private sector must collaborate to close infrastructure gaps, protect critical ecosystems, and build resilience at every scale. Multi-stakeholder engagement is not optional; it is essential to address the complexity of water challenges in a changing climate.

The clock is ticking. As glaciers retreat and extreme weather events intensify, Bolivia faces critical decisions that demand immediate action. Yet, within this urgency, lies the opportunity to shape a water secure future that is resilient, equitable and sustainable through proactive, inclusive and science-based action.

The authors:

Paula Cecilia Soto Ríos is coordinator, Graduate Unit of Chemical Engineering, Universidad Mayor de San Andrés (UMSA) and Chair of Governing Member (GM)-Bolivia

Paola Andrea Alvizuri Tintaya is researcher, Universidad Católica Boliviana San Pablo and media and Young Water Professional (YWP) GM-Bolivia