By Richard Forster

Two projects bringing safe water supplies to African countries have been selected as Lighthouse Activities of the Momentum for Change initiative of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

At a ceremony held during the COP21 Climate Change Conference in Paris in December, Solvatten’s solar water heater and the Lifelink Water Solution were recognized for their innovative use of technology to provide safe water for low-income people in Kenya and Uganda while at the same time contributing to a reduction in carbon emissions.

Swedish company Solvatten’s solar water heater has reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 22,000 tonnes in four years in Kenya, by removing the need for families to burn wood or charcoal to heat water. Lifelink, which is provided by Danish manufacturer Grundfos, uses a smart card system to offer rural and urban residents access to safe water from a dispenser backed by submersible solar-powered pumps.

With 783 million people lacking access to safe water globally, the two projects were among sixteen initiatives chosen from over 450 applications by the UN not only for their contribution to tackling climate change but also because of their scalability.

Solvatten’s founder Petra Wadström hopes that the emissions reduction award will open up new avenues in her search for funding and partners to spread the adoption of her invention.

“If we can subsidise Solvatten by monitoring the carbon we are reducing it is a way to make it possible to reach out on a big scale,” Wadström told The Source. “If you can use it for two or three years, you can recoup the investment.”

Wadström’s story is one of a determined and brave inventor, who with a background in research and art, was able to conceive of a portable, solar-powered water heater after a visit to Indonesia in 1998 brought home the problems for women in particular of providing clean water for their families.

Instead of spending hours tending a fire to heat water, women can use the portable heater several times a day with clean hot water stored for use.

“Instead of being afraid someone will steal your equipment you can put it indoors for the night and people have made insulating bags so they can store hot water till the next morning,” said Wadström. “So it frees up a lot of time for women not to struggle by the fire all the time and will help lift women out of a tough situation.”

The power of solar energy

On her return to her native Sweden, and with her own money, she launched a prototype in 2003 and through a meeting with Anna Tibaijuka, then Executive Director of UN- Habitat in Nairobi, was able to secure seven months’ funding to trial the heaters and test the results in Nepal in 2007. Manufacturing on a larger scale began in 2009.

Solar energy can be more effective than chlorine in treating contaminated water because the ultraviolet rays destroy the DNA linkages in microorganisms preventing them from reproducing and rendering them harmless. Pasteurisation through the heat from the sun enhances the treatment process and makes Solvatten extremely effective at preventing waterborne diseases such as cholera, dysentery and typhoid. Tests by the US Environmental Protection Agency in 2014 showed that Solvatten was able to eliminate the most resistant parasites, viruses and bacteria.

“We asked them to test Solvatten in California for both parasites and bacteria,” said Wadström. “They added 10 millions of e coli and for parasites and rotavirus they found Solvatten was at the highest protection level which the WHO has. It is amazing the sun can do this without chemicals being added.”

But Solvatten is not only about cleaning water it also provides a warm supply to families. Wadström says that having warm water is important to the dignity of individuals and its health and economic effects should not be underestimated. If families can bathe properly and regularly, it leads to better healthcare and she points to a reduction in eye infections and skin infections in Kenya as well as farmers earning more money by providing longer lasting milk, as they can use the heated water to clean udders on their cattle.

“You need to see the difference with having just chlorinated water: it is day and night,” added Wadström. “We in Europe are used to having hot showers and red and blue taps but no one is talking about this part of hygiene and the hot water need for poor people.”

Over 42,000 Solvatten units are now in operation in Kenya, Uganda, Pakistan and Nepal and Wadström has just returned from refugee camps in Jordan where she took some example units over to show the effectiveness of her solution.

Despite its scalability Wadström says it is hard to convince donors of the investment value of Solvatten, as they think too much in silos or need quick, short-term fixes.

“If you look at the cheapest solutions, you don’t look in a refugee settlement for something that is long lasting, you look for chlorine for maybe three months but the reality is that people are living in those camps for generations,” commented Wadström. “When I discussed this not long ago at SIDA [Swedish development agency] if we could fit into this programme with Power Africa to give access to renewable energy they said no because it was about electricity . But what do you use electricity for? ‘We give light to people’. But that is not enough. This is one of the blind spots I think from the decision makers.”

Grundfos, which is promoting Lifelink as a sustainable solution in Kenya, Uganda, Ghana, Thailand and India, has ambitious goals to scale up the use of its system through its partnership with the children’s charity World Vision International. Through their collaboration, the aim is to provide clean water to two million people in five years through the installation of over 1000 new pumps. Much of the success for Lifelink stems from partnerships with such international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), which have mobilised rural communities and trained them in hygiene.

World Vision International will use Grundfos solar pumps and dispensers to provide mechanised systems, which mean more people gaining water access quicker and a more sustainable model using solar instead of diesel pumps.

“What we are trying to do with World Vision is not only transactional in terms of selling them pumps but value creation which means capacity building,” explained Rasoul Mikkelsen, Director of Global Partnerships for Grundfos Lifelink. “They are looking to reach one person every ten seconds by 2020.”

Reaching out with innovation

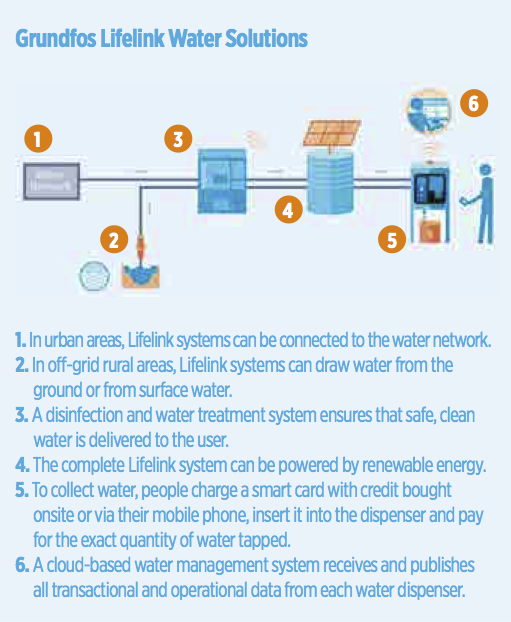

Lifelink was recognized by the UN for its strong record of success in Kenya with 40 systems currently serving 100,000 people, relying on the use of Mpesa’s mobile phone technology for payments from handsets. A person can obtain water using a smart card by sending an SMS with payment when they are at a water kiosk with the credit being transferred to the smart card in the Lifelink dispenser. The operator of the water system, which may be an NGO or in urban contexts, a utility, is able to manage all revenue including smart card movements and water consumption through a desktop solution (See graphic).

“We built the technology around non-bankable people. So even very poor people will pay for the water because they know the service is there and because utilities are sure they will get their money, they will bring the price down of water because they are actually collecting money to make it more affordable for poor people,” explained Mikkelsen.

The pilots for Lifelink were launched in the rural area of Musingini in Kenya in 2009. A second business model is to work with utilities in urban areas where previously it was difficult to collect revenue and Lifelink is now being employed in the informal settlement of Mathare in the capital city of Nairobi.

“We believe that through partnerships we can also build the capacity of the utilities: it is not only transactional but we also understand their pains,” said. Mikkelsen. “This technology gives them [utilities] the tools to collect revenue in an efficient way and gives them the incentive to provide water services in slums. There is very little opportunity for mismanagement or corruption.”

Beyond utilities and NGOs, Grundfos is looking for new business models to scale its innovation. In India there is potential for young professionals to set up businesses as social entrepreneurs to operate Lifelink systems for the provision of water.

“Entrepreneurs have discovered that through this innovation they can maybe have a cluster of four or five villages where they can provide water for the people and create an income,” said Mikkelsen, who says that they are also exploring using a leasing model in India. The company is now targeting the use of Lifelink in Bangladesh, Myanmar and Cambodia in Asia-Pacific and Malawi and Nigeria in Africa.