By Pritha Hariram*

As we mark the international year of Wastewater, I’m taken back to my childhood crossing the Adayar Bridge in Chennai, India, in an air-conditioned “Ambassador” (the iconic Indian car that served as high-end taxis in the 80s). The airtight car windows and cool air-conditioning provided little protection from the stench coming from the river, reduced to trickle passing under the bridge on its way to making a very undramatic entrance into the Bay of Bengal.

On that hot summer day as I sat in my “protected” Ambassador with my family, the Adayar river, once the economic and cultural backbone of Chennai, was reduced to nothing but an active landfill and untreated wastewater discharge zone. To complement the stench, the sight was unbearable, resembling a large septic tank of sludgy consistency filled with debris. Thankfully, the story of Adayar and its estuarine extension, the Coum river, does not end there.

Fast-forward to 2012, and a large, citizen-driven petition led by local NGO, the Consumer Action Group, successfully persuaded the Tamil Nadu government to take action. This has resulted in the development and implementation of a large-scale restoration programme that began with the construction of over 300 sewage treatment plants. This was followed by an eco-restoration phase, including the plantation of mangroves along the estuary stretch of the rivers. The programme is now in its third phase with continued eco-restoration and de-silting of the riverbeds.

This combination of nature based solutions and grey infrastructure has become a flagship project for Tamil Nadu, and serves as an eco-restoration model to be replicated in the rest of the southern Indian state. It’s also a timely reminder for the rest of the world, of what can be achieved when citizens and governments come together to press for change.

In 2015, 193 countries jointly adopted the Sustainable Development Goals, pledging to provide universal access to adequate sanitation and to halve the proportion of untreated wastewater being discharged into nature. To achieve these ambitious goals, a rapid transformation and significant investment is urgently needed.

Globally, the vast majority of wastewater, as high as 80 percent, is discharged untreated into our waterways, where it creates health, environmental and climate-related hazards. In communities around the world, the result is often rivers and waterways being reduced to the condition of the Adayar and Cooum rivers of the 80s.

When it comes to sanitation, some 2.4 billion people, 1-in-3 of the entire population of the planet, are still without sanitation facilities. This includes 946 million people who defecate in the open. This results in 842,000 people in low- and middle-income countries dying as a result of inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene each year.

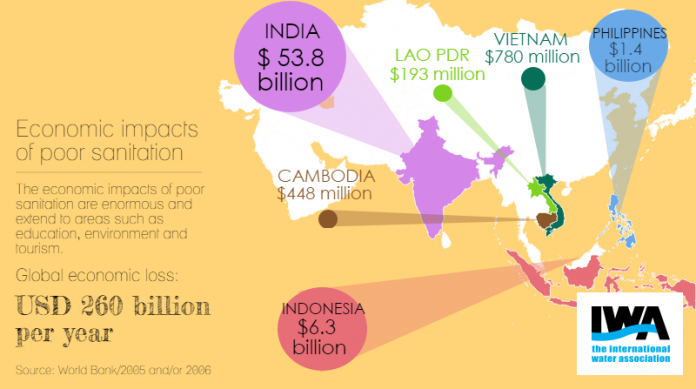

The economic impacts of this are massive, and have cascading impacts on other sectors such as health, education and tourism. The World Bank estimates the annual economic loss due to poor sanitation to be US$260 billion a year. Another layer of complexity is that sanitation services are significantly undermined by an enormous human resources capacity gap, and a poor supply of professionals will compromise the ability to achieve the SDGs.

Yet much progress has been made around the world. Between 1990 and 2015, 2.1 billion people gained access to improved sanitation. In China, wastewater treatment efforts between 2000 and 2014 increased the number of treatment facilities in cities from 480 to 3720–an additional 36 million citizens per year receiving wastewater treatment. Elsewhere, bold policies and investments have achieved transformational change. The impact of the EC Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive in England and Wales saw investments of £9.2 billion in sewerage services between 1990 and 2000.

Sharing success stories can help reverse a lack of vision and governance to inspire sustainable sanitation and wastewater management, where stakeholders co-create a shared vision. As with the story of the Adayar and Cooum rivers, we know it can be done, and now is the time for a huge scale-up of our efforts.

To do this, a paradigm shift in our approach to wastewater and sanitation is needed, and the water sector has a pivotal role to play. This cuts across multiple interlinked areas, whether our human rights obligations, or the resource recovery of wastewater to enable a transition to the circular economy. This will allow cities, soon to be home to two thirds of the global population and increasingly the engines for the future economy, to unlock their potential to drive sustainable sanitation and wastewater management.