Mandela’s least known legacy may be his Working for Water programme, which employs thousands of marginalised people to clear invasive plant species, securing precious water supplies in perpetuity

By Alex Hetherington*

Having eradicated apartheid and sown the seeds of real democracy. Nelson Mandela had to confront a looming threat to the security and hope of South Africans.

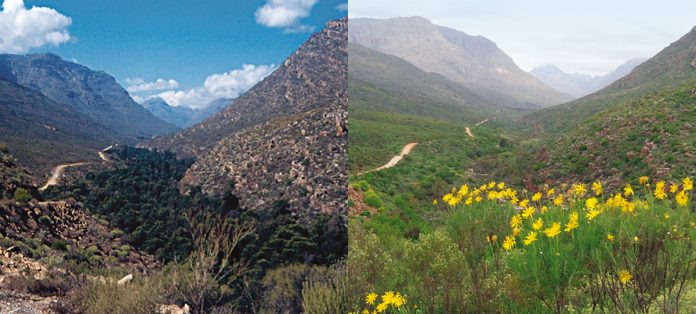

Each species in isolation–and there were over 80 species–may have seemed little more than a noxious nuisance. But together they had grown to cover 16 percent of the country’s land area, and the cumulative effect was to reduce annual streamflow by 7 percent.

Recognising this risk, Mandela’s team began, through labour-intensive plant removal, to claw back 4 percent of this water, and make it newly available for human use. The result led to an inter-governmental, multi-million dollar national response known as the Working for Water (WfW) programme.

This approach could also make sense in other parts of the world. Christo Marais, Chief Director of Natural Resource Management Programmes, of which the largest is WfW, urges governments to consider upstream alien plants in the water supply/demand equation.

“The degradation and transformation of wetlands, riverbanks and flood plains leads to a reduced amount of water being absorbed into the natural systems and later released into the aquatic ecosystems,” he says.

A national problem doesn’t arise overnight or by accident. European settlers had deliberately introduced many plant species over three hundred years to support dune stabilisation, woodlots, and tannin production. Acacias, wattle, pine and eucalyptus have become among the most prominent species. Under dry windy conditions, a single Australian bluegum (Eucalyptus salinga) can absorb seven hundred litres per square metre of leaf cover each day. Invaded landscapes can annually consume 300-400 millimetres (mm) more than natural grassland, cutting runoff by 3-4,000 cubic metres per hectare.

South Africa is caught between diminishing rainfall (now 464mm/year) and a growing population of 55 million. It cannot afford to sacrifice water to alien plants.

Indeed, there’s less than nothing to spare. The country’s 2013 National Water Resource Strategy stresses that the country’s financially viable freshwater resources are already “fully utilised”, putting its 4,395 dams under immense pressure as agriculture and urban demand runs apace. As 8 percent of the country’s landmass produces more than half its runoff, every drop must be harnessed for productive use.

“The water needs to be captured before we lose it,” says Marais. “We can’t allow the natural ecosystems to clog with invasive alien vegetation.” He adds that every 3-10 hectares of densely infested land, once restored to full ecological function through alien plant eradication, releases enough water to irrigate a hectare of land in perpetuity.

After amassing two decades of proof, WfW has become a poster child for innovative, strategic, and scalable responses to invasive vegetation– augmenting supplies in water scarce regions. But Marais says this isn’t an either/or approach to water security.

“It is important to understand that the eradication of aliens works in tandem, and supports, necessary infrastructure,” he says. “All we are doing is improving the efficiency of existing water supply systems.”

As a supplementary service WfW can focus on water replenishment while exploring the wider social benefits of a plant-clearing public works programme.

The WfW model has attracted foreign visits and requests for presentation worldwide. While replicated nowhere in its exact form, other public employment programmes adapt its restorative focus. China’s “Grain for Green” project rehabilitates degraded mountainous areas while Ethiopia leverages labour, policy and official support to restore watershed services. Yet any city, agency or nation seeking to adapt the WfW recipe must grasp the five ingredients that underpin it.

First, before eradicating existing alien species, stop new arrivals. National and local policy prohibits the continued introduction of invasive plants into the natural landscape, coupled with land use incentives against their detrimental effect. Trained customs officials practice stringent control at South Africa’s ports of entry.

Second, strategic investment can yield multiple outcomes. By working directly with land users, WfW can direct government, corporate and development funding towards the most critical areas where eradication of invasive vegetation can yield the highest water resources. In the arid, northern part of the country, the state electricity utility, Eskom, led partners to invest US$3.3 million by clearing plants in order to enhance water availability and the productive land use for communities upstream of a newly built coal-fired power station.

Also, research and development pays surprising dividends. For example, biological control of alien infestations may prove the most natural, safe and affordable tool. Officials annually invest US$3.5 million in the strictly managed introduction of host-specific species that drastically reduce seed production and even, in some cases, kill off the alien species.

You also need to encourage diversified spin-offs. A strong focus on value-added enterprises from the WfW programme has germinated numerous small businesses. These convert cleared vegetation into building materials, energy sources and other economic activities. Rather than simply dispose of dead vegetation, people recycle it, even in the manufacture and distribution of school desks to the national Department of Basic Education.

A final step is to highlight how plant eradication generates skills, income, and jobs in urban and rural areas alike. Against a national 30 percent unemployment rate, WfW forges linkages between ecosystem services and steady careers. Those benefits stand out as a double revelation. Since inception, Marais’ programme, of which WfW is part, has created more than 225,000 person-years of employment, with opportunities for the poorest and most marginalised. Indeed half of all recent WfW employment opportunities go

to women, more than sixty percent are under 35 years old, and military veterans and parolees often find work through the programme.

Even WfW proponents stress that alien-plant clearing is not a panacea for all water supply ills. Nor does it play the lead. Its importance lies in the ‘best supporting actor’ role: improving the performance of existing infrastructure. But if strategically manipulated, ecosystem service programmes like WfW can offer far wider socio-economic benefits than merely building and filling dams.