IWA recently held a webinar on how the influence of Indigenous Peoples could help the world meet the Sustainable Development Goals. Erika Yarrow-Soden highlights some of the key messages.

On 9 August, IWA held a webinar on ‘Embracing Indigenous perspectives to achieve Sustainable Development Goals’ to mark the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. Commemorated each year in recognition of the first meeting of the United Nations (UN) Working Group on Indigenous Populations, held in Geneva in 1982, this is an important day for raising awareness of the needs of Indigenous Peoples – who are among the most disadvantaged people in the world – and recognise the measures that are required to protect their rights and maintain their distinct cultures and ways of life.

Indigenous Peoples have sought recognition of their identities, their ways of life and their right to traditional lands, territories, and natural resources for decades. Yet, throughout history, these rights have been violated. With an estimated 476 million Indigenous People in the world, living across 90 countries, and representing 5000 different cultures, it is now widely recognised that these voices must be heard. Moreover, they have much to teach about the environment and its protection, living with and protecting the environment for generations.

Against that backdrop, IWA’s Specialist Group on Sustainability in the Water Sector was proud to organise this webinar with the aim of highlighting Indigenous perspectives on the water sector, in order to gain understanding, most particularly with regards to progress – or lack of it – in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the necessary drivers required to accelerate progress that respects the rights and unique needs of Indigenous communities.

Respecting a history of nurture

Water is a crucial element for all life and all types of human communities, whether Indigenous or non-Indigenous. It plays a significant role in the economic, environmental and cultural aspects of all of our lives. It is vital. Yet, Indigenous Peoples have seen their ways of life threatened, through pollution, failure to recognise their human rights, and lack of political will to right the wrongs of the past and implement legislation to restore their freedom to live according to their traditions in a clean, conserved environment. The irony of this lack of insight is that Indigenous Peoples embrace and apply traditional methods and solutions to manage many of the water-related risks that the world is currently facing, based on generations of knowledge lived close to nature, and for many a life lived in marginal and adverse environments.

Sadly, these long-established systems of values, knowledge and practices have been largely overlooked by the water sector and fail to inform modern water management approaches. But it is now beginning to be realised that it is time for the voices of Indigenous Peoples to be heard and valued; that their experience warrants more attention; and that this demands that Indigenous Peoples are involved in development processes at all levels – local, national, and global.

Including the voices and experiences of Indigenous Peoples from different parts of the globe, this webinar aimed to play a part (if only small) in a movement for change, by providing the opportunity for speakers to discuss the challenges and their perspectives on how Indigenous knowledge can contribute to the water sector’s delivery of SDG 6 and the broader SDGs that focus on development and quality of life. The presentations and discussions aimed to: identify the challenges faced by Indigenous Peoples related to the water sector, such as dealing with water-related risks and unequal access to water resources; learn from the positive examples of Indigenous practices that have successfully addressed water challenges; identify actions to include Indigenous Peoples in the drive to achieve the SDGs; and promote a more equal and inclusive water sector by gaining awareness of new approaches and perspectives.

Water is not a commodity

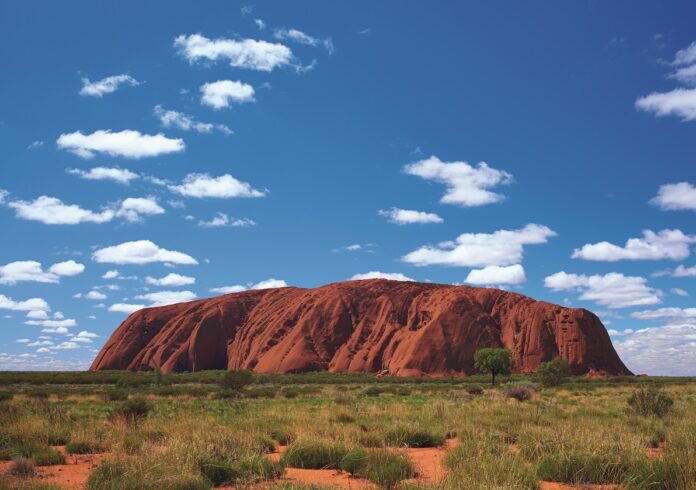

Bradley Moggridge is Associate Professor at the Centre for Applied Water Science at the University of Canberra in Australia. Describing himself as a “proud Murri from the Kamilaroi Nation”, Moggridge is a researcher in Indigenous Water Science. “We need to think about how we look at water,” he said. “We view it as a commodity, but it’s so much more than that. Without water we die. We need to include Indigenous People in the way we adapt to climate change. We are still not thinking about the next drought. Or how Indigenous knowledge can shape the way we manage our land.”

Moggridge explained that he entered research in Indigenous Water Science because he was “tired of non-Indigenous people telling our stories”. Continuing: “I can’t speak for Indigenous Australia. There are more than 300 different language groups and more than 600 dialects, so we’re very diverse… But traditional water knowledge is embedded in our lives. Water is protected by Lore in our songs, dances, the dreaming, stories, and art. I’m hoping to pressure the learned academies to consider cultural knowledge as evidence rather than myth and legend. So that our knowledge is culturally validated.

“Our land and water were given away. Rivers were modified, over-extracted and polluted. We were put in reserves. Put on the outskirts of towns. Waters were diverted away from rivers and wetlands. Now, modern-day pollution is impacting our water places. Tap water in more than 500 remote Indigenous communities isn’t tested regularly and often isn’t safe to drink. We are being left behind. How can Australia meet its SDGs if it doesn’t collaborate with communities to mend these failings in a culturally appropriate way?”

Transparent, open systems

Largely neglected from decision-making processes, it is understandable that Indigenous Peoples frequently feel ignored and railroaded by industry, especially those who rely heavily on natural resources. To establish trust, it is essential sectors develop transparent and inclusive systems that respect Indigenous Peoples in their decision-making.

Troels Kaergaard Bjerre, project director for VandCenter Syd, a water utility company in Odense, Denmark, explained how the company had based its sustainability plan on the objectives of the SDGs, initiating a comprehensive cross-organisational project using the SDG framework for corporate sustainability. Through the development of an SDG assessment tool to determine decision-making, the company was able to demystify how priorities were arrived at, provide transparency, and increase inclusivity through a system that gave attention to ‘Who is at the table’, and whether their opinions are heard or ignored.

“Our corporate goals take an outside approach that forces us to consider what is necessary rather than what is convenient,” explained Kaergaard Bjerre. “Decisions shouldn’t be based solely on costs and efficiency. We have an obligation to make the world a better place. We must serve the community.”

A model with political sustainability

Isaac Piyako, Indigenous Leader of the Ashaninka Ethnicity in Brazil and first Indigenous Mayor in Brazil, explained that Indigenous People had limited land and were struggling to maintain their traditional ways of life because of the impacts of industry and the failure of public policy to take the concerns of Indigenous People into account. He said: “As mayor, I was able to have some influence – coordinating a solar project and a sanitation project to stop the pollution of rivers. But it is very difficult.

“Policy is in the hands of the government. We have some forest cover and rivers, but these rivers often start in industrial places and now our rivers are no longer safe to drink or bathe in. We’ve done all we can to maintain our connections with water and nature. We consider the conservation of water to be a spiritual responsibility. We have tried to preserve as much as we can, and we are now fighting for everything our ancestors worked so hard for. We need laws that do not damage the Indigenous population. We want to work together to get funding for a model that has political sustainability, so that we can train people about our ancestors’ way of life.”

Beyond compartmentalisation

The empowerment of Indigenous People and their ability to influence development is critical to achieving the SDGs and to miss the opportunity to work with Indigenous People to find sustainable ways to resolve the global water crisis would be a calamity. “Science is new,” said Dawn Martin-Hill of the Mohawk, Wolf Clan, and one of the founders of the Indigenous Studies Programme at McMaster University in Canada. “Our knowledge goes back thousands of years.”

Noting that water and food were previously bountiful, Martin-Hill highlighted how much the Great Lakes have been impacted by pollution.

“Our people are having to stand up to the unwise practices of colonialism that have scorched the Earth around us. The problem with the SDGs is that they are very compartmentalised and Western. Concepts from the West don’t help. We don’t own water; we require water. It is a source of life. Without it, there is no future. We need to change the mindset and become sovereign thinkers on how to protect water, not water sovereignty.”