By Hassan Aboelnga

Many cities today are at risk of running out of water, with water availability now cited as one of the greatest risks to business continuity and growth. It is very clear that the way water is managed today in many parts of the world poses serious risks to human well-being and sustainable development. Imagine going through your day with limited access (only for a couple of hours per day or a couple of days per week) to store water in your home for drinking, cooking, washing or bathing. The condition where water is provided for a limited period of time is called Intermittent Water Supplies (IWS), and affects at least 1.3 billion people around the world.

The scale of systems operating under IWS conditions is expected to intensify as water demand continues to increase due to rapid urbanization and on the other hand water supplies tend to decrease due to climate variability thus posing a great challenge to achieve urban water security and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Under conditions of water resource shortage many countries have turned to IWS policies as a means of controlling water demand and expanding their existing domestic water supply. Unfortunately, adoption of intermittent water supply systems aggravates urban water insecurity, as it fails to consider the impact on the condition of the water supply systems and the detrimental effects on public health. IWS fails to provide citizens with safe and sustainable water services and to protect them from water-related calamities.

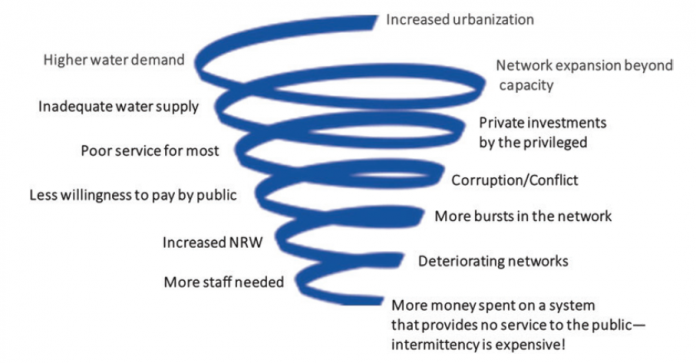

IWS can be seen as a downward spiral (schematically shown below) where increased urbanisation leads to higher water demand. Water utilities tend to respond with network expansion, which often takes place after poor planning, and extend the network beyond capacity, thus lowering the quality of service for consumers. This leads to an inadequate water supply for towns and agglomerations, which may entice people (mostly the privileged) to take matters in their own hands and proceed with private investments that will improve their service.

IWS service costs more than continuous service.

Intermittent hours of water supply force customers to rely on black-markets or informal vendors, often serving higher-income citizens, thereby exacerbating inequalities among users. IWS service costs more than continuous service, and users bear the brunt of having to pay more to access water services via alternative routes. It also weakens the social contract between governments and their communities when water utilities fail to deliver basic water services, perpetuating a downward spiral of water insecurity and fragility in many developing countries. For example, riots broke out in Algeria in 2002 and in Bolivia in 2000 over water shortages.

Impacts of climate change on IWS can act as risk multipliers in fragile contexts, contributing to conflict, violence, or migration.

Water quality problems due to the potential suction of non-potable water by negative pressures, biofilm detachment, and microbial re-growth especially when static conditions occur. Roof tanks often encourage bacterial re-growth.

IWS holds back gender equity. As the task of providing water for households falls disproportionately to women and girls, especially in rural areas. IWS locks women in a cycle of poverty and it is hard to imagine that women’s and girls’ experiences will improve without intentional efforts to deal with intermittent water supply.

Achieving a paradigm shift from IWS to continuous supply is only possible by changing the way we manage water today. As Buckminster Fuller said, “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” – The numerous problems associated with management and operation of distribution networks under IWS as well as the critical challenges entailed in moving to 24/7 water supply forms the core objectives of the IWA IWS Specialist Group (IWSSG). The work that is undertaken by the IWS Specialist Group will help to better understand what the root causes of intermittent supply are and how to apply, in a simple and practical manner, solutions which will assist water utilities operating their networks under intermittent water supply and to document in a structured manner cases that were successful to move from IWS to continuous supply in a sustainable manner.

The IWA IWS Specialist Group stresses the importance of addressing the challenges of intermittent water supply in the policies and plans of sustainable water management, which interconnects with all sustainable development goals.

IWA IWSSG aims to provide leadership in the development of effective and sustainable international best practice to improve the Level of Service in Intermittent Water Supply.

How to get involved? Join our IWA Connect group, LinkedIn group and Facebook Page and check out our news bulletin

Hassan is a PhD researcher at Cologne University in Germany with a particular interest in urban water security issues including non-revenue water management and integrated water resources management. Hassan is certified project management professional (PMP)® and has been an active in the international level as a young water professional in issues of water security, climate change and youth advocacy. He has a strong academic background in engineering and management, including international professional trainings in water related issues. He has been an active member of many international organizations including International Water Association.

Hassan is also member of the IWA IWSSG Management Committee and IWA IWSSG YWP Liaison