Half of all electricity in California’s water sector is used by utilities, and that adds up to 10 percent of total state usage. To clean up its act and neutralise its carbon footprint, Sonoma County had a choice: invest in costly hard infrastructure, or negotiate less expensive energy from the pool of renewable sources emerging on the local grid. By James G. Workman

No one forced Sonoma County Water Agency (SCWA) to change its ways.

There were no public threats, no lawsuits. Regulators made no demands on the agency, which serves 600,000 people on the west coast of the US. In fact, the most striking thing about its metamorphosis, free from the taint of fossil fuels, wasn’t the speed, the savings, or the sense of local pride it instilled. It was how it had been 100 percent voluntary.

Change began a decade ago, when then-chief of SCWA, Randy Poole, summoned his team into a room. There, Santa Rosa’s Republican mayor Jane Bender and leading climate advocate Ann Hancock issued a challenge: Why don’t you leverage all your technological resources to mitigate climate change?

Mitigate? Back then, if water professionals thought of climate at all, they saw it as a volatile force–think droughts, floods, endangered species–to which you adapt.

But California’s new Governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, had just put a spotlight on all emission sources in the state. And for utilities, the data wasn’t pretty. US municipal water systems burned 138 TW hours of electricity, at 3.5 percent of the total consumed. California’s water-related energy devours a fifth of the state’s electricity, a third of its natural gas, and 333 trillion litres of diesel fuel every year.

The Golden State’s water was polluting its air.

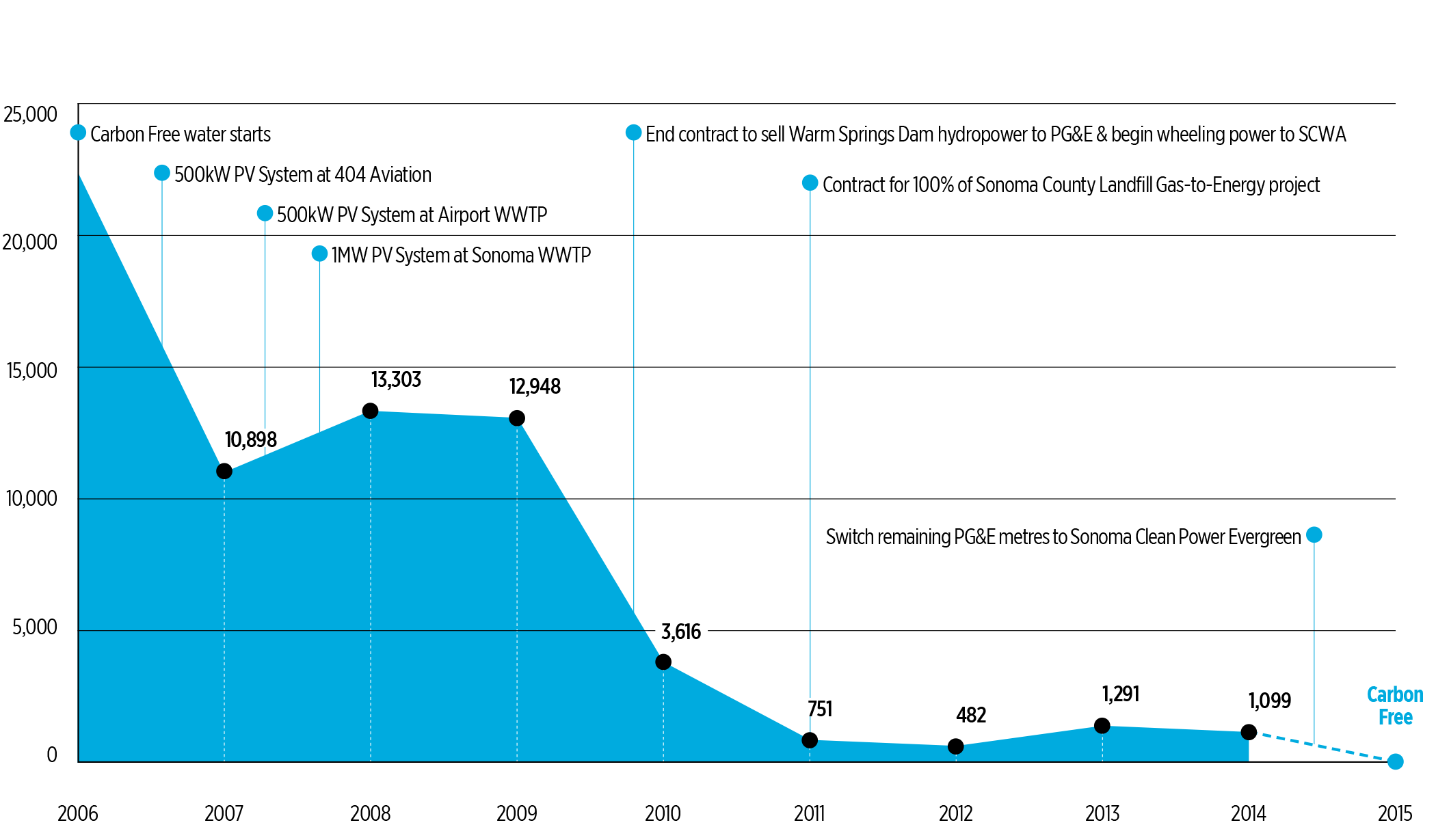

Sonoma’s Water Agency prided itself on a culture of innovation, testing approaches other utilities would never touch. So, Poole locked his team in a room with academics like energy specialist Daniel Kamen of the University of California, Berkeley and Robert Wilkinson of the University of California, Santa Barbara to examine energy in the water supply chain. They emerged with a rough plan and a new slogan: Carbon-Free by 2015!

Carbon-free water means no fossil fuels are burned in order to provide water services, including capturing, cleaning, and delivering drinking water to taps. This year, Sonoma’s Water Agency was able to announce that it had reached its target by contracting all its energy needs from renewable resources.

“Like any goal, we set a high bar and then tried to figure it all out,” recalls SCWA Deputy Chief Engineer Cordel Stillman, who was promptly ‘voluntold’ to implement it. “I didn’t think there was a chance in hell we were going to get there but by taking advantage of all the tools we had, it turned out to be relatively painless.”

A new report, Clean Energy Opportunities in California’s Water Sector, described how water and wastewater utilities can become leaders in the state’s clean energy transition. Still, it was largely conceptual. With SCWA’s achievement, observers began celebrating. Juliet Christian-Smith, a climate scientist with the Union of Concerned Scientists, stressed that SCWA’s biggest advantage was that it had began to explore opportunities early. That brought it “to the forefront of efforts to lower the carbon footprint of water,” she said writing on the Equation blog, and demonstrated “how the water sector can be a bigger part of the clean energy transition.”

I didn’t think there was a chance in hell we were going to get there but by taking advantage of all the tools we had, it turned out to be relatively painless

How did it happen?

Stillman initially came at it from a technical, engineering mindset. He sought first how to design, build, and operate 12 MW of new clean, renewable constant power that peaks with demand in summer time. Within 18 months he’d installed 2 MW of solar panels, and started exploring other options to fill the missing 10. Anaerobic digesters? Floating solar? Wave energy? Geothermal? Wind power? “Anything we could think of, we took a run at,” he says, only to confront the usual challenges of base versus peak demand, intermittent supply, lack of storage, and high costs. Stepping back, he began to widen the circle of thinking to look outside the technocratic box. By setting up group resource pools with neighbouring utilities, drawing on their reserves, and negotiating for bulk in advance, SCWA was able to get more–and more reliable–clean energy, for less. “It ultimately came down to membership in water and energy resource pooling that allowed more flexibility,” says Stillman.

As a wholesaler, SCWA leveraged its membership in the regional Power and Water Resources Pooling Authority (PWRPA), to contract independently for power.

The clean energy market, relatively young, at certain times had more supply than demand. So as an early mover in this thin, regional market, SCWA could negotiate a customised blend of renewable or carbon-free sources, when it wanted. It tapped irrigation districts for winter access to clean generation from the Western Area Power Administration; secured hydroelectric power from SCWA’s own Warm Springs reservoir; and methane-generated power from the County landfill.

Those clean energy sources covered 95 percent of SWCA’s load. But frustratingly, it found, like someone struggling with a diet, that the last five percent was the hardest part to lose.

The clean energy market, relatively young, at certain times had more supply than demand. So as an early mover in this thin, regional market, SCWA could negotiate a customised blend of renewable or carbon-free sources, when it wanted

To shed the final tons of carbon, and not break its budget, SCWA helped form a broad consumer market for green energy options. The water agency negotiated renewable options from Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), the state’s biggest energy grid, and took advantage of lower costs. “Sonoma Clean Power” meant end users could switch meters over to evergreen, renewable supply. As a result, its carbon-free water is not as cheap as before, but still 17 percent cheaper than PG&E.

Two pleasant surprises arose on the road to decarbonisation. The first was how exclusive long-term contracts could lock up renewable energy from local projects, yet be renegotiated when prices dropped. The second was leveraging its own assets; SCWA could purchase, sunset, and reserve hydropower from Warm Springs Dam, and exclusively wield that power to itself.

“Most people managing their utility’s energy accounts don’t realise how much clean, carbon-free energy is available out there,” says Stillman. “They don’t know what to ask for, or how to use their market share on the demand side to negotiate good, long-term deals.”

SWCA has set the bar for other utilities to follow suit. “This achievement is a powerful proof of concept showing how the water sector can be a part of the state’s ambitious climate efforts,” says Christian-Smith.