In a rapidly urbanising world, a lot of attention is rightly focused on the challenges surrounding transport, housing, energy and employment. Yet many cities with steeply rising populations often neglect a resource that is essential to sustaining all activities in a city:water. Nick Michell highlights how cities can work towards achieving sustainable water systems and the benefits that will bring

Water as a risk needs to be understood and managed to ensure the security of people’s habitats and livelihoods. Historical development pathways are often not appropriate for planning future urban water systems, considering the uncertainties of climate change and rapid population growth. Planning these systems with increased modularity and reduced dependencies will enhance the ability to react to unforeseen trends and events.

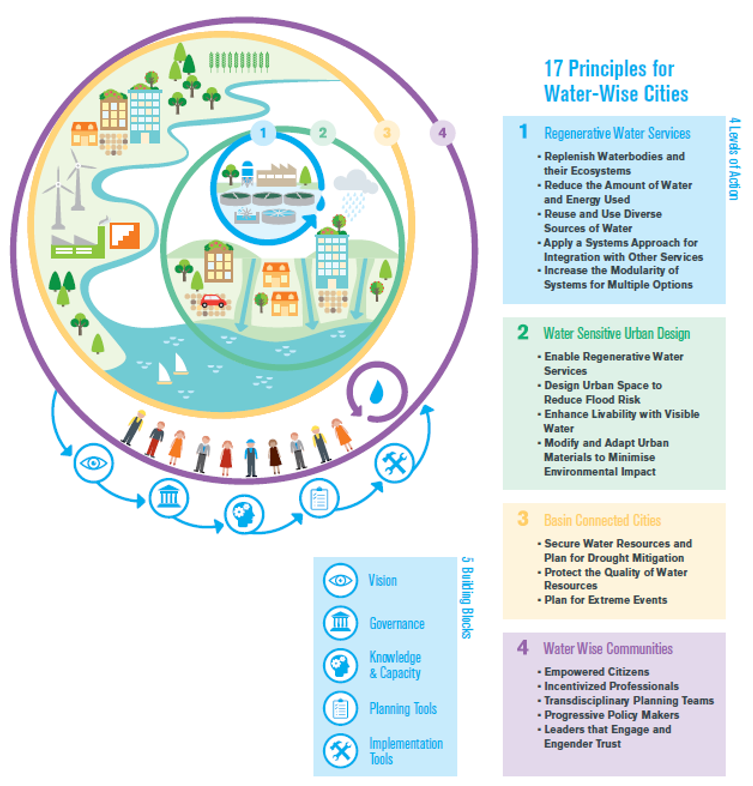

This is why the International Water Association (IWA) has developed the Principles for Water-Wise Cities, which were unveiled at the Association’s Global Congress last November. The Principles aim to inspire urban leaders, water managers, individuals and other stakeholders to collaboratively find solutions on water management challenges, and to implement water-wise management strategies through a shared vision that will enable the development of flexible and adaptable cities.

“Cities striving to achieve sustainable urban water, are cities where all urban waters are used and managed by water-wise communities: citizens, professionals, leaders all acting in a wise way towards their water resources,” says Corinne Trommsdorff, Manager, Cities of the Future Programme, IWA. “They are cities that are connected to their basins to maximise security from floods and droughts, as well as protect the quality of their freshwater source. They are cities built in a way that is sensitive to water issues so that short-term risks are minimised and resources are preserved, while liveability is improved as a co-benefit.”

Creating water-wise cities is a huge task due to the slow pace of planning, unclear lines of governance which makes stakeholder collaboration difficult, and the low level of citizen engagement. Water-sensitive cities are great places to live, where innovation, social cohesion, creativity and culture flourish, but achieving this requires harnessing the power of collaboration with adapted governance.

The Principles for Water-Wise Cities are structured along four increasing levels of action (each enabled by the next level), accompanied by five building blocks through which the urban stakeholders can deliver sustainable urban water, becoming a water-wise community.

A number of partners, from local government and the public and private sectors have joined forces to endorse the Principles and collaborate on supporting cities as they work to become more water resilient.

“In a world of limited resources, we will need innovations in two key areas to meet the SDGs–cities and water,” says Randolf Webb, Senior Analyst for Strategy and Business Development at Xylem, one of the endorsers. “Cities are often an efficient place to deploy capital towards sustainable development, and water is one of the few sectors where investments can drive positive environmental, economic, and societal outcomes.”

The Principles provide cities with a roadmap and tools to capitalise on the opportunity identified by Webb.

“There will be challenges such as balancing priorities and financing initiatives, but with cross-sector collaboration and sufficient political will, I’m optimistic that we can get there in my lifetime,” he adds.

Collaboration

Roles and responsibilities for managing water vary depending on the city, but are often spread across different levels of government and a range of stakeholders such as service providers, public authorities and river basin organisations. Even in very decentralised examples, national governments have a role to play in setting proper incentives and frameworks for urban water governance. Clarifying specific responsibilities at every level of government can help identify potential disparities, duplications or grey areas and help in coordinating the actions of multiple players in an efficient and inclusive way.

The Principles advocate a consistent approach to sustainable urban water management, which aims to galvanise action so that city leaders engage in policy discourse and partnership development with leaders in the environmental, agricultural, energy and waste sectors.

“National economies are built on strong cities,” says Councillor David McLachlan, Chairman of the Environment, Parks and Sustainability Committee, Brisbane City Council, another endorser of the Principles. “If cities wish to remain prosperous and resilient, it is essential that they have a robust framework for sustainable urban water management, with support from all levels of government. This is particularly important in our climate, where there can be long dry periods that require us to manage our water sparingly. It may, however, require new governance and finance frameworks to achieve water-wise cities.”

Water in cities is affected by decisions made in other sectors and vice versa. It is essential to ensure that water is recognised as a key factor of sustainable growth in cities and such a strategic vision is essential for strengthening policy coherence for an integrated urban water policy.

“A governance structure that enables collaboration is critical and many cities still have a lot of progress to fully facilitate this,” adds Trommsdorff. “The OECD Water Governance in Cities report is a good framework for cities to transition to water-proofing all their decisions, even the ones, which are not initially related to water, but that have a more or less direct impact on waters in the city. In terms of financing, there is also a need to evolve and improve towards more circular economy models.”

Building on a survey of 48 cities from OECD countries as well as emerging economies, the Water Governance in Cities report shows that significant progress has been achieved in urban water management, but important challenges remain. For instance among the cities surveyed, the average share of wastewater treated was 90 percent in 2012 compared to 82 percent in 1990; while per capita domestic water consumption decreased by 20 percent between 2000 and 2012.

However more than 90 percent of the cities surveyed reported ageing or lacking infrastructure, which threatens universal coverage of drinking water and sanitation and diminishes the capacity to protect citizens against water-related disasters.

Governance issues

As emphasised in the OECD report, policy responses need to be tailored to a given city’s needs, while aligning with national goals and priorities. Water is a local issue and the way in which it is governed in a city can differ, not only nationally, but also on a district level, making it critical to have an understanding of specific regional challenges, and to involve local stakeholders in public policies.

Milwaukee, in the United States, has become a centre for water innovation due to leadership from The Water Council, an international organisation headquartered there, which is comprised of a partnership among business, academic, and government leaders.

After several decades of decline, the city’s population has stabilised and is now back on the rise, forcing Milwaukee into expanding its effort to maintain and replace its traditional water infrastructure. At the same time, the city is expanding green infrastructure as well as new water technology demonstration sites in its four eco-industrial districts, including the Water Technology District, Harbor District, Menomonee Valley, and 30th Street Industrial Corridor.

One of the emerging policy and governance issues, however, relates to the condition of sewer laterals and drinking water service lines. Historically, private property owners were responsible for the condition of sewer laterals (pipes that connect homes and businesses to the sewer mains.) Private property owners are similarly responsible for drinking water service lines (pipes that connect buildings to the public infrastructure which begins at the property line). Sewer laterals that develop leaks and cracks can allow groundwater to enter the sanitary sewer system and potentially overwhelm it in large storms.

“The issue of lead drinking water service lines in older properties has also emerged as a public health concern,” explains Erick Shambarger, Environmental Sustainability Director, City of Milwaukee. “The city and sewerage district does not have much control over the condition of these private laterals and drinking water service lines under the historic utility model. However, the condition of laterals can have a collective impact on how well the sewer and stormwater utility functions. Lead in drinking water service lines can periodically affect the quality of drinking water at the tap.”

As private entities often do not have the means or will to replace this ageing infrastructure on private properties, Milwaukee is exploring policy options to provide financial assistance to replace these laterals and service lines over time.

Overcoming issues related to who does what, at what level of government, and how and why public policies are designed and implemented, is often a thankless task for many cities and certainly hinders the route towards a sustainable water system.

One solution to counter this is to create a centralised organisation that is solely responsible for water services in the city, as has been successfully done by Amsterdam in the Netherlands. Waternet was formed as a joint venture by the City of Amsterdam and the Regional Public Water Authority Amstel, Gooi en Vecht, and has control of all public water services in the city, which are financed by dedicated local and regional taxes.

Waternet takes the lead in new collaborative platforms working across urban challenges such as climate adaptation and the circular economy. The Amsterdam Rainproof platform is a collaborative network of public administration entities, entrepreneurs and citizen initiatives. Together, they are committed to making Amsterdam more resilient to extreme rainfall, both on small and large scales, in buildings and gardens in public areas.

“From a Dutch perspective cities and regional water authorities have a lot of responsibility and power over its water services,” says Roelof Kruize, Managing Director, Waternet. “I strongly believe in the strength of non-profit, publicly owned and locally rooted water utilities, which are able to collaborate with other public administration entities, entrepreneurs and citizens in working on cross-cutting themes such as sustainability and resilience.”

Raising awareness among citizens

Capacity is often the Achilles’ heel of local governments with 65 percent of surveyed OECD cities reporting the lack of staff and managerial competencies as a challenge. These inadequacies can in turn directly affect the mindset and behaviour of citizens, who put faith in the knowledge and proficiency of city officials to provide water services.

It is important to raise awareness among citizens and policy makers of the water-security dangers to trigger policy and behavioural change, and engage with stakeholders, including property developers and long-term institutional investors, to build consensus on the acceptable level of risk and secure willingness to pay for water services.

“While we have made great progress with our water management across the 59 municipalities of Lyon Metropole, like the redevelopment of Grand Parc Miribel Jonage to include natural flooding areas upstream of the city to better protect it against flooding from the Rhône, we still need to improve our work with raising awareness among our residents,” says Elisabeth Sibeud, Head of Studies, Grand Lyon Water Department. “It’s important for them to understand the water challenges that we are facing and, for instance, better manage rainwater on their own properties. We are working and having discussions with other cities about how they have managed to do this successfully.”

Technology is one way of not only educating citizens but also empowering them to make change and save money. Currently, many in western economies just turn on the tap for a drink or a shower without giving it a second thought. Providing people with more information about their water bills will help them manage their usage, and assist water authorities in reducing overall demand.

Smart cities can move towards a point where technology in individual homes will enable people to have real-time understanding of their water use throughout the day. They’ll be able to see how much water is used in each room of the house and at which times, through a smartphone app. Households will also be able to identify water leaks that they don’t currently know exist, which costs both them and the water authorities money.

Co-benefits

Even if initially targeted at simply delivering basic services, there are numerous co-benefits of integrating water into urban planning, which will improve liveability in a city.

A typical example is stormwater management using green infrastructure with the primary objective to reduce flooding, which also contributes to the wellbeing of urban dwellers with green parks and roadsides reducing the heat island effect, or through enhancing food security with urban food production. Cities could also coordinate with energy and telecom services to share trenches for pipes and wires. In this case, the co-benefit of integration is reduced costs and construction disruptions.

of the Environment, Parks and Sustainability Committee, Brisbane City Council

Clean waterways can provide waterfronts for public spaces fostering a sense of place and social equity, while buildings can be designed that need less water, as they harvest rainwater, reuse greywater, and produce energy from organic wastes, offsetting expensive centralised infrastructure expansion to provide water and collect and treat waste.

“Water defines Brisbane as a river city,” says David McLachlan. “Inhabitants expect adequate clean water to be delivered affordably. They also expect access to a healthy environment that supports a water- based outdoor lifestyle. The people of Brisbane enjoy recreation along our river and local waterways, and harvested rainwater, providing ‘fit for purpose’ water to their irrigated gardens, shadeways and local parks.”

Sustainable urban water is about all people in a city having access to water services that are regenerative, in other words, that do not take more nor send back to the environment more than it can give or take. Regenerative water services are also more modular and adaptive, so that when a disaster strikes and changes occur, water services can bounce back or spring forward into supporting basic needs.

City leaders need to engage in policy discourse and partnership development with leaders in the environmental, agricultural, energy and waste sectors. Policy makers and city service providers must embrace inclusive decision making that engages and empowers urban citizens to establish water-wise communities.

Collaboration is essential, but beyond collaboration, regular communication across sectors and industries is critical. Each of the entities involved in creating a sustainable water management system must make decisions based on timely and accurate data, which then needs to be shared.

In most cities the key is not in changing the way institutions are organised but in making sure they work together towards a common goal. And herein lies the challenge because cross-sectoral or cross-institutional collaboration is very difficult because it requires people to think beyond their own assigned workplan or targets.

“I think the key is really in collaboration,” concludes Trommsdorff. “Whether the city itself owns more of the water-related responsibility or whether it lies with other entities, doesn’t matter so much. Water is so cross- cutting, that what will make the difference is getting all the people that have a connection to water to develop a collaborative mindset.”