Water-related data is transforming the high-stakes metrics of adaptation

By Ilyse Veron*

New York City’s Carnegie Hall attracts the world’s top musicians but last October, an anxious audience heard insurers, scientists, and military strategists sing a darker tune, warning of an urban cacophony of unnatural disasters.

“Water issues are the front lines of climate impact,” said retired US Navy Captain James Goudreau. “Some cities will have too much and others won’t have enough. Flooding events aren’t going to be limited to coastal cities, as weather events overwhelm the capacity for urban areas to handle rainwater or river flooding events.”

On stage, Lloyd’s insurance market practice teamed up with the American Security Project to host climate, financial and antiterrorism experts on how to build urban resilience to the coming confluence of extreme weather events that are not just painful, but expensive.

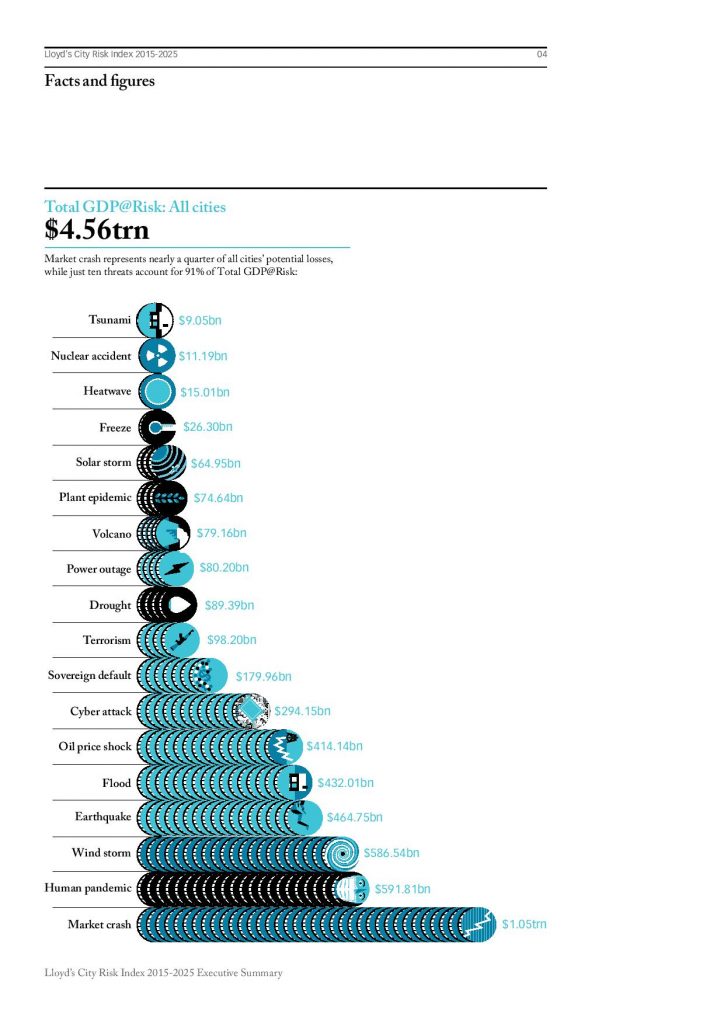

City Risk Index of

301 leading cities estimates that from 2015 to 2025, natural threats alone will put US$2.43 trillion at risk

According to the CEO of Lloyd’s, Inga Beale, these catastrophes cost cities about US$10 billion a year in the 1980s. Today they erode US$50 billion. Building to a numerical crescendo, Lloyd’s City Risk Index of 301 leading cities worldwide estimates that from 2015

to 2025, natural threats alone will put US$2.43 trillion at risk. “If something doesn’t make us stand up and take action that should,” warned Beale.

Her firm’s index, based on original research by the Cambridge Centre for Risk Studies, aims to “prompt innovation–among insurers, governments and businesses to help improve resilience, mitigate risk and protect infrastructure.”

At the top of Lloyd’s list of urban risks was a market crash, followed quickly by floods, droughts, freezing, heatwaves, windstorms, and pandemics. Complicating matters, certain urban risks compounded one another, creating regional instability, which could force a military response.

Goudreau, formerly acting deputy assistant secretary for the US Navy, described how military bases adjusted to the “wicked problems” of drought and flood risk, working for years to reduce usage, increase re-use of captured water and adapt their bases for that environment using a portfolio of approaches like xeriscaping.

“But government action is only a part of the story since the losses caused by climate impact will be far beyond what federal and local governments can pay,” said Goudreau. “Industry must and will play a pivotal role in building resilience.”

Few disagree. But how can the private or public sectors pin down and quantify something as vital, yet abstract, as resilience? It’s a slippery term, scaling from the psyche to the atmosphere. At the epicentre of all this is cities.

Michael Berkowitz, President of the 100 Resilient Cities network, which was created by the Rockefeller Foundation, recently described measuring resilience as among the great challenges of our time, adding that urban areas provide an optimal scale for such metrics. Arcadis has developed its own Sustainable Cities Water Index, with a subset of 50 resilient cities in 31 countries. These efforts combine accessible data, defined geography, political accountability, and demographic outcomes. Berkowitz’s supports Chief Resilience Officers and programmes in 100 cities worldwide (as referenced in The Source Issue 4), which help set priorities.

“If there’s one US region that should concern all Americans,” warns Roger Sorkin “it’s Hampton Roads in southeastern Virginia, home to our largest naval base and a number of other critical military installations.” Sorkin leads the American Resilience Project and directed Tidewater, a film that tells this story.

When the moon orbits closest to the earth, he points out, seas swell in a ‘king tide’, and coastal waters seep onto the streets, tying up traffic near base where a quarter of all US Navy vessels are stationed. The military relies upon the region’s seventeen local jurisdictions to maintain roads, sewage, water and electricity. Impacts of recurrent regional flooding “affects military readiness,” says Sorkin, and can limit “the US’ ability to deploy and maintain forces.”

In response, the region has taken a proactive approach, building resilience to sea-level rise and other environmental threats in ways that set an example for other vulnerable regions.

Alyson Myers, who runs the Fearless Fund, grew up in Norfolk, Virginia and now worries about how to plan for new building. “Once you’ve seen it flood, [you know] it will be back,” she cautions. “And buildings, unlike water, do not move.” To help absorb such recurring shocks, Myers finds aquaculture can absorb carbon and polluted runoff while protecting against Virginia’s rising sea.

That sea has risen a foot over the last century outside of Carnegie Hall, New York. It was a slow, silent process that Hurricane Sandy dramatically punctuated. “New Yorkers are able to absorb what happened and move on,” says Dan Zarrilli, New York’s Chief Resilience Officer. Still, lingering threats keep him up at night: more flooding, rain and heat, followed by second order effects of food security and migration patterns. How can he rank these risks?

Enter big data. People are harnessing the rich power of information from many sources to assess the extent of sea level rise, the amount and quality of freshwater, and the best processes for wastewater treatment and removal. They also use big data to plan ahead, to manage growth and aging infrastructure. In the Obama administration NOAA, FEMA and others began upgrading standards and increasing actionable communications.

The next step is to translate all that data into action. Goudreau, now head of energy and climate for Novartis, told The Source he worries that many public statements are “either very technical or very dramatic,” and thus often inaccessible or disregarded out of hand. “We haven’t really convinced other folks outside of our community of interest that this is a present day issue that impacts them personally,” adds Goudreau.

Water professionals, he said, can become more pro-active about the dual crisis and opportunity. For any community, water resources can be both an amenity and a threat, and lessons can be learned from around the world.

In the Netherlands, the Building with Nature programme makes “room for the river” by investing in raised driveways, permeable structures, and canals that allow water to flow. In southeast Florida, mayors have created local and regional climate change task forces, committed to fostering “climate resilience” and coordinated a policy agenda with education and outreach efforts, including “D-rop”, a rapping drop of water, as its mascot.

Nor is it just affluent cities of Europe and North America that are galvanising data to boost adaptive capacity. West Africa’s shoreline is eroding by as much as 23-30 metres in a year. As the coastline collapses, roads, homes, and schools are lost in Togo, Benin, Cote D’Ivoire, Mauritania and São Tomé and Principe, as well as Ghana and Senegal. Flash floods affect more than 500,000 people, and “when expatriates return to Togo’s coast to visit their childhood homes,” reports Dahlia Lotayef of the World Bank, “they are astonished to see that communities have literally been washed out to sea.”

A response has begun. In Lomé, Togo, a regional workshop of stakeholders took stock, quantified data, and emphasised that technical training is needed to buffer these coastal communities. As they undertook training, they found prospects and partners for risk-reducing investment under the umbrella of a blue economy.

Resilience emerges through a systems-based approach. That’s why the recent IWA Principles for Water-Wise Cities combine data, technology and behaviour. Rich data lays a

solid foundation for investment and gathering both information and funds can’t happen too early. All levels of government find it hard to act fast when budgeting and executing major projects. “If impacts are happening today, and are going to get worse in the next five to ten years, that is quicker than many communities can get bond issuance, raise capital and then award contracts for execution in time to prevent damage in their communities,” comments Goudreau.

But as tides rise, time runs out. “When you feel risk is close enough to touch you,” warns Goudreau, “there’s no time to ask for money to deal with it.”

Institutional Resilience

Systems re-thinking requires a revolution from within

Before society can absorb external shocks from escalating drought or floods or rising seas, it must first adapt internally, re-aligning diverse institutions to share both risks and rewards. In some ways, that’s even more complicated.

Environmental advocates say degraded ecosystems leave urban areas vulnerable to disasters. Engineers often view “natural infrastructure” solutions as uncertain and unpredictable. Can both sides integrate their thinking and efforts?

Yes, say water professionals, but only once they respect each other’s values. Integration emerges as engineers gain real yields from too-often vague ‘ecosystem services,’ and ecologists provide precise data about the performance of green infrastructure projects.

That ‘sweet spot’ may be closer than we think, said Shannon Cunniff, Environmental Defense Fund’s Director of Coastal Resilience. There’s already a movement, in fact, as the Corps of Engineers new nationwide general permits include “living shorelines”.

Over coffee in a Washington DC café, Cunniff demonstrates how re- vegetating slopes, setting back levees, and green-scaping city development can all measurably, and economically, reduce flooding. Re-introducing mangrove forests, in addition to nursing wild fisheries, may also buffer the effects of a tsunami from racing inland, while healthy coral reefs and wetlands can help absorb the shock of waves. Restoring and preserving natural defences helps to create multiple lines of defence that work together to lessen the chance a violent storm delivers a knockout punch.

In each case, engineers and conservationists can improve habitat to decrease their vulnerability to extreme events. But collaboration begins only if they stop speaking past one another, imprisoned by their own vocabulary, standards, culture, and agendas.

Internal integrity can emerge from the bottom up. In 2016, Pritzker architecture prize winner Alejandro Aravena popularised the process of “participatory design”. Chile’s Aravena has been committed to building low-cost housing after natural disasters. His solution goes beyond robust construction materials or solid engineering. He works with people to put “forces of life” at the innermost core of a community’s architecture, for example, harnessing an intact, open forest or wetland to help protect their urban landscape.

Institutional alliances can also be driven by a shared national imperative. As exemplified in Virginia (see main story), military, business and civilian groups work for a shared outcome. Cunniff helps team members bridge the gap, and says certain qualities equip leaders for success.

These include a multi- or inter-disciplinary background; a willingness to put yourself in uncomfortable positions; systems thinking; an ability to learn and use a new vocabulary; curiosity and eagerness to translate develop ideas across sectors; acumen for team building; and interest in combining diverse cultures, strengths, and world views. If you can define shared challenges in this way, you’re a long way towards resolving them.