With the world seeking a push on sanitation, as part of the drive towards achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), non-sewered sanitation has a vital role to play, writes Dhesigen Naidoo.

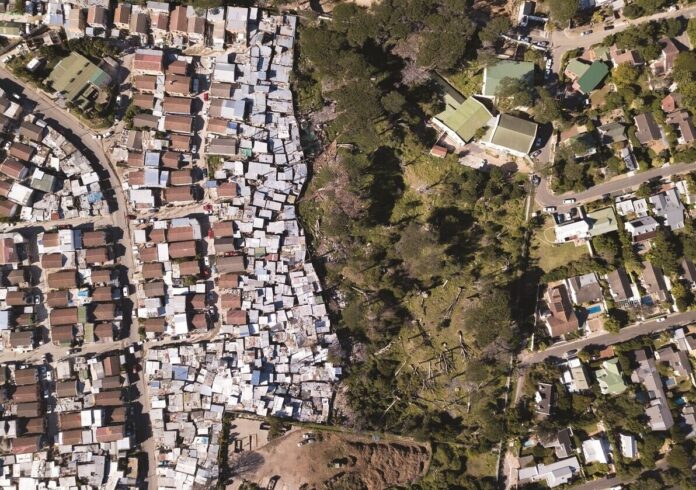

In February 2021, the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) issued a damning report on the Vaal system in the Gauteng Province of South Africa. The SAHRC report described the Vaal as “polluted beyond acceptable standards”. The conclusion was that the flow of sewage into the Vaal constituted a human rights violation. This followed protests in Cape Town – the so-called ‘poo wars’ against the inadequate sanitation servicing of the townships in the city’s peri-urban fringe. Yet Johannesburg and Cape Town are among the wealthiest city regions in Africa. In fact, they count in the richest 1% of cities in the world. So, we can see that the old narrative of poor sanitation being only a challenge in the poor world needs a major revision. It also calls for a new strategy.

Worldwide, 2.3 billion people lack basic sanitation services, with 892 million still having to resort to open defecation. The net impact is not only a limiting of people’s dignity, it also has a major impact on health, with more than 800,000 people dying from WASH-related diseases each year, accounting for 60% of all diarrheal deaths. In fact, only 45% of the global population (3.4 billion in 2019) use safely managed sanitation services. We have a 55% challenge to solve.

Against this backdrop, the SDG6 Global Acceleration Framework (GAF), part of the wider UN SDG Decade of Action, was launched by UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres and UN Water in 2020 to drive progress with the core water-related Sustainable Development Goal. The five accelerators included in the GAF reflect the complexity of achieving universal access to sanitation beyond approaching it as a challenge of last mile coverage.

There is also a connection for non-sewered sanitation (NSS) in each of these accelerators, presenting an opportunity for it to drive progress on SDG6.

Innovation

New solutions are coming through channels such as the very successful Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s Reinvent the Toilet Challenge (RTTC). The RTTC has mobilised a global network of research institutions and, very importantly, innovators and entrepreneurs, through initiatives such as the South African Sanitation Technology and Entrepreneurs Programme (SASTEP). This has introduced a suite of new sanitation technologies and solutions currently in demonstration in many parts of the world. A central feature of these ‘new sanitation’ solutions is that they are either dry or low-flush solutions and all are completely non-sewered.

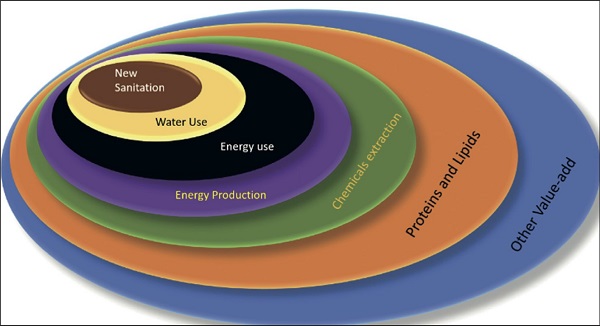

The merits of NSS are now well known. Breaking through the barriers of high capital costs associated with sewered systems in favour of localised waste treatment and combining this with low water use make for a compelling argument. With the removal of the need to convey waste over vast distances to centralised wastewater treatment plants, there are also significant energy savings. A further boon is the great potential to beneficiate the waste (Figure 1).

“The old narrative of poor sanitation being only a challenge in the poor world needs a major revision. It also calls for a new strategy”

The safe beneficiation of human waste creates important possibilities for the building of businesses and the creation of sustainable livelihoods and jobs. While the world collectively scrambles for economic recovery from the downturn resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, NSS represents an attractive prospect to edge closer to the sanitation goals in SDG6, in a water-wise manner that has the potential to assist with economic recovery and growth.

Governance

UN Water expressed a deep appreciation that a major hurdle in effecting transformation in water and sanitation is the legislative and regulatory environment.

A critical contribution in this domain has been ISO 30500, the ISO standard for ‘Non-sewered systems – Prefabricated integrated treatment units – General safety and performance requirements for design and testing’. This defines the requirements for the quality of the NSS system outputs for solid and liquid discharges, as well as odour, air and noise emissions. ISO 30500 also defines the standards for safety, functionality, usability, reliability and maintainability of the system, as well as compatibility with environmental protection standards.

In a very conservative global water sector, this is a great leap forward. ISO 30500 was adopted in October 2018 and was quickly followed by the adoption of national standards in Senegal and South Africa in 2019. This, combined with the faecal sludge management standard ISO 24251, provides a regulatory platform that has the potential to catalyse the rollout and upscaling of NSS as solutions of choice to extend safe and dignified sanitation coverage for the 2.3 billion people that currently fall outside the universal coverage net envisaged by SDG6.

Finance

In a weak global economic environment with a modest economic recovery outlook, as expressed by many pundits, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), major pots of finance for new infrastructure projects appear limited. NSS has the distinct advantage of coming in at costs that are quantums lower than traditional sewer systems. NSS also has the added advantage of offering new innovative business development models such as social franchising, as has been demonstrated in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. The real promise on finance comes from the beneficiation of waste, which can attract significant pools of venture capital as we start realising the potential of new industrial and business platforms in this domain.

Data and information

Engaging the toolbox of the ‘fourth industrial revolution’ is critical for the water and sanitation sector, for accessing the next level of the digital and artificial intelligence revolution. The decentralised and localised nature of NSS holds the promise of creating critical data points for environmental indicator surveillance in many domains. The obvious are the water and health domains, but these are also accompanied by security status mapping, better data for spatial planning and development, and many others.

Capacity and capability

It is abundantly clear that water security and sustainable sanitation requires a much wider range of talents. In addition to the technicians and engineers, there is a dire need for talent in information technology, behavioural sciences, economics, marketing, communication, and many other areas.

It looks overwhelming, especially for a sector such as water – deeply entrenched in its traditions and practice. New sanitation offers the perfect pilot to develop this new water and sanitation team – embracing its new dimensions and developing not only the new capacities and capabilities required, but also the models to engage this more manageably for the broader water sector as a whole.

We must also recognise that this new sanitation paradigm has a multiplier effect beyond the water sector. A positive chain reaction is possible out of the initial investments and achievements of new sanitation as it is embodied by NSS (Figure 2).

The value proposition of NSS is promising, and the International Water Association’s creation of a specialist group able to develop this business case further provides an important signal in this respect. The SDG6 Global Acceleration Framework has, in the shape of NSS, a candidate catalyst that can act at multiple levels. What we do in the rest of this Decade of Action will determine the state of sanitation globally for the next century. We must build back better and build forward greener.

Dhesigen Naidoo is CEO of South Africa’s Water Research Commission, member of the Presidential Climate Commission, President of HumanRight2Water, and founding member of Water Policy Group.

Figure 1. Non-sewered sanitation has a high beneficiation potential. The use of waste slurries as organic fertilisers is well established. Waste also has high energy generation potential through biogas capture as well as liquid fuel. The extraction of high-value proteins, peptides and lipids are now emerging from the laboratory to complement the chemicals extraction that is already being industrialised.

Figure 2. The multiplier effect of new sanitation. It remains our best chance to realise the sanitation universal coverage goal of SDG6, which in turn expands the frontiers of dignity – particularly for the world’s poorest. The impact on hygiene and health security will be prolific, as major disease burdens will be drastically reduced, improving both quality of life and productivity. It also has the potential to introduce the much-needed new paradigms for water and energy. All of this should reflect positively on the Happiness Index of countries, regions and the world.

“The old narrative of poor sanitation being only a challenge in the poor world needs a major revision. It also calls for a new strategy”