Experience is growing with use of specially developed guidance to overcome local misunderstandings or concern over what the human rights to water and sanitation entail. By Louisa Gosling, Tseguereda Abraham, Rob Fuller and Carolina Latorre.

The world, through the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), has promised to provide universal access to clean water and sanitation by 2030. We are woefully behind. Globally, one in 10 people do not have clean water close to home, and one in four are without a decent toilet of their own. Universal access will not be achieved for hundreds of years at current rates of progress in some countries, such as Niger, Madagascar and Ethiopia.

Access to clean water and decent sanitation are recognised by the United Nations as human rights, reflecting the fundamental nature of these basics in every person’s life. How, then, can this help drive progress with the SDGs?

International law says it is the state, as ‘duty bearer’, that has an obligation to guarantee these rights equally and without discrimination. The right to water entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use. The right to sanitation entitles everyone to have physical and affordable access to sanitation in all spheres of life that is safe, hygienic, secure and socially and culturally acceptable, and that provides privacy and ensures dignity. Some of the most important stakeholders in achieving these rights are utilities and regulators, as well as the government and civil society.

The pressure is therefore on local and national authorities around the world to make sure suitable infrastructure and processes are in place for the effective management of human waste, and for universal access to clean water.

The pressure is therefore on local and national authorities around the world to make sure suitable infrastructure and processes are in place

To help governments fulfil their responsibilities for realising rights to clean water and decent sanitation, water professionals and practitioners in the International Water Association (IWA) – together with WaterAid, WASH United, the Institute for Sustainable Futures, End Water Poverty, Unicef, the Rural Water Supply Network (RWSN) and Simavi – have evaluated the human rights principles and translated them into practical guidance.

Support for local governments

One such set of guidance is the ‘Making Rights Real’ approach, released in 2016 by WaterAid and several partners. A collective change of mindset is needed to recognise that each day someone is living without water and sanitation, their human rights are breached.

The ‘Making Rights Real’ approach is aimed at some of the most important actors in the water and sanitation arena – local government officials – to help turn human rights as a moral and legal obligation into practical action.

In many countries, the responsibility for ensuring access to water and sanitation has been decentralised, from national to local government. This means local government officials are the duty bearers on the front line. They have closest contact with the people who need water and sanitation – the ‘rights holders’.

Local governments often fear human rights as a potential cause of conflict if people demand, as a right, services that local government does not have the capacity or resources to provide. Reframing the discussion in terms of human rights, however, can encourage local officials to engage far more with the communities they serve. The result is better services, healthier outcomes and increased prosperity.

The guidance works by helping everyone to have a clear understanding of their responsibility for ensuring all have water and sanitation, while applying the human rights principles of equality and non-discrimination, sustainability, accountability, participation, and access to information. It helps government officers and communities discuss together how to overcome the immense challenges in a way that fosters more constructive collaboration to achieve the shared goal of universal access.

Supporting utilities and other service providers

Another important set of guidance is IWA’s manual on human rights. While the state is the duty bearer with overall obligation, all institutions working on any aspect of drinking water and sanitation have a responsibility to understand and apply the human rights framework to their work.

At a local level, local governments are normally the duty bearers. However, it is often via utilities and other professionalised service providers that the human rights-based approach is manifested.

The manual, published in 2015 and translated into Portuguese, French and Spanish by sector practitioners, introduces a human rights perspective that adds value to decision-making in the daily routine of operators, managers and regulators. Creating such an enabling environment is the first step in the process towards progressive realisation of the rights. Allocation of roles and responsibilities is the next step, in an updated institutional and operational set-up that helps apply a human rights lens to the process of reviewing and revising the essential functions of operators, service providers and regulators.

The manual has provided a welcome addition to the discussion on what needs to be done to ensure universal access to water and sanitation under the human rights framework. Only by everyone fulfilling their role and taking their responsibilities seriously can universal access be ensured.

Progress in Ethiopia

The ‘Making Rights Real’ approach was developed from interviews with local government officials, in 12 countries, about their challenges and aspirations, and what motivates them to try to reach everyone with WASH services.

This partnership-building initiative is already making a tangible difference, such as in Ethiopia, where its roll-out started this year. Here, WaterAid applies a ‘systems strengthening’ approach, working in different ways to help government transform the institutions, policies, infrastructure and resources to ensure WASH services and behaviours are inclusive and sustainable.

The ‘Making Rights Real’ materials, translated into local languages, have guided discussions with local government officials in regions that face severe capacity and resource constraints. WaterAid Ethiopia held a workshop for officials in the remote district of Gololcha to discuss the human rights principles from their perspective. One local government official said: “When building our team, we have learned to think of better participation. Having the community feel they are the real owners of the project helped us work better to solve problems and increase belief and hope in our activities.”

The workshop and materials helped the local government officials to reflect on their challenges and understand their roles and responsibilities. They discussed how they could benefit as individuals from adopting the human rights principles. They also realised it could help them draw on others for support for capacity and resources. It could help improve local government responsiveness to people’s demands and that, in turn, would support them in problem-solving, to make best use of scarce resources.

“It is very enlightening to reflect on our own roles; it is an opportunity to think about new ways to address our day-to-day challenges,” said Habtamu Dendea Jara, utility office head in Gololcha, Ethiopia.

Others in the workshop stated: “Engaging leaders and people with influence when doing our work can make a great difference. Leaders can help channel more resources and promote achievements to help us demonstrate resources are well spent, and to get communities’ support to help us work better.”

Expanding interest

The experiences emerging from Ethiopia and similar initiatives are providing evidence of the value of the rights-based approach – which is why WaterAid presented the latest findings at this year’s Stockholm International Water Week. It is also one of the reasons WaterAid will be participating in the IWA Water Development Congress & Exhibition later this year.

The materials are starting to be used in Bangladesh, by Simavi, and in Bhutan, by SNV, supported by Juliet Willett’s team at the Institute for Sustainable Futures in Sydney, Australia (see box, below).

Use of the materials has been tested in India. Other countries that have used the materials and the approach more generally, discussing with local government officials their roles and responsibilities connected to the rights, include Burkina Faso and Ghana. There have also been expressions of interest from Uganda, Cambodia and Pakistan, after the Ethiopia experience was shared with those involved in the susWASH project (washmatters.wateraid.org/suswash).

For regulators and service providers, there are no absolute values that apply globally for implementing the human rights criteria. Governments will have to establish national standards in line with local resources. Regionalised dialogue offers an opportunity to discuss geo-targeted, realistic and relevant actions. The work of IWA members addressing regulation is taking root in Latin America and the Caribbean. The region is a benchmark for progress in terms of explicit recognition of these rights in constitutional laws – for example, Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua and Uruguay – and judicial advances and regulation of the sector (Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica and Mexico). The challenges in these countries are mainly focused on implementation.

Building on the findings and recommendations of the IWA manual, IWA is joining forces with the Inter-American Development Bank to work in collaboration with the Association of Regulators of Water and Sanitation of the Americas on a project that will identify the regulatory challenges in realising the rights in the region, as well as the drivers, potential synergies and trade-offs to meet them. The project will provide the baseline – from a regulatory perspective – for development of strategies for realisation of these rights at a country/local level and recommendations for action at the policy level, supporting professional and capacity development.

Action on inequality

The importance of universal access to WASH cannot be overstated. It underpins the human rights agenda and stretches across health, nutrition, education and equality, as a fundamental building block to a healthy and safe future, including for the most marginalised.

Part of the reason for such a shortfall in access is a lack of local accountability, poor understanding of where the duty lies to provide these services, and a lack of resources to act upon that duty. Bringing together all the actors, using human rights as a framework, is helpful in addressing the enormous challenges we face.

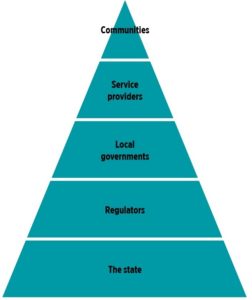

The work of IWA and WaterAid addresses the complex actions needed to activate all the ‘layers’ in the pyramid to realise the human rights to water and sanitation – and, ultimately, achieve the sustainable development we want. The examples above demonstrate actions are possible at various levels and around the globe at different latitudes, and they have the potential to work synergistically. As the IWA Lisbon Charter notes: “Effective service provision relies upon the collective actions of interdependent stakeholders.” Tools are available; more examples of implementation are needed.

Collectively, we must do more than simply continue; we must accelerate progress. If we do not, inequalities will only deepen and human rights will be denied.

Louisa Gosling, quality programmes manager, WaterAid UK

Tseguereda Abraham, head of sector strengthening, WaterAid Ethiopia

Rob Fuller, water sector adviser, WaterAid UK

Carolina Latorre, senior officer, water policy and regulation, IWA

As part of WaterAid’s participation in the IWA Water and Development Congress & Exhibition, it will develop these ideas with IWA and other members of Making Rights Real in a workshop.

For more information on WaterAid’s work, see washmatters.wateraid.org/publications/embedding-and-integrating-a-human-rights-based-approach

The IWA manual is available at: iwa-network.org/publications/manual-on-the-human-rights-to-safe-drinking-water-and-sanitation-for-practitioners

The relevance of rights to water professionals

Juliet Willetts, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney

Water professionals, as technical experts, may think human rights have little to do with them. This is far from the truth, however. As people with knowledge, networks, authority and expertise, we have inherent responsibility and skills to contribute to achieving the right to water and sanitation for all people.

We all choose where and how to place our efforts. A human rights approach clarifies the priority to address, as a starting point, existing inequalities in access to water and sanitation services without compromise. It is no longer acceptable to choose the low-hanging fruit to support change.

In Asia and the Pacific – where we, at the Institute for Sustainable Futures, work – we address the human rights through research partnerships with governments at national and subnational levels, as well as with civil organisations. Our research repeatedly asks questions of ‘who benefits’ and ‘who has voice’, expanding the evidence base on existing inequalities, and testing and supporting policy and practice shifts towards serving all. We are currently working with WaterAid in a global consortium on ‘Making Rights Real’, which engages local government officials on the rights, and with SNV Development Organisation on integration of the rights into their programming approach in Bhutan.

Achieving the rights requires the combined efforts of the private sector, governments and communities to reverse current trends of increasing inequalities. Every water professional has a responsibility to consider their place and role in the sector, to reflect on how their work aligns (or not) with human rights to water and sanitation, and to take appropriate action.

In meeting SDG 6 on water and sanitation, and using human rights principles of non-discrimination and accountability, we have a much-improved chance of meeting other SDGs, such as ending poverty and reducing inequalities.

Action needed by all actors

Leo Heller, UN special rapporteur on the human rights to water and sanitation

Ensuring access to safe drinking water and sanitation for everyone, without discrimination, is the core state obligation under international human rights law. So, it is essential that the most disadvantaged and marginalised groups get special attention and are not left behind.

For this, states’ obligations unfold into obligations and responsibilities to public authorities at the subnational level, service providers, regulators, and other stakeholders involved in service provision.

While activists, legislators and courts from all over the world push forward the formal recognition of those human rights, each actor must play its role and abide by them without delay. Compliance with the human rights framework means, for instance, that service providers are not allowed to disconnect users that fail to pay their bills because of an inability to pay, and must search for alternative ways to reduce default rates.

For regulators, it entails the obligation to monitor affordability effectively and, when rates are too high or increases are needed for cost recovery, they should turn to governments and suggest the implementation of different forms of subsidies.

In summary, human rights require all key actors to replace the hegemonic logic of the water sector, including first those who live in vulnerable situations.

Adhering to human rights principles and implementing their core content is as challenging as it is urgent – but change is possible with some creativity and audacity. Do it the rights way!