By Sushmita Mandal*

As a fast growing economy, urbanising at an even faster rate, India is already water stressed. The severe drought of 2016, which affected more than half the country and saw some of the highest temperatures ever recorded, only served to highlight an already serious problem. Water scarcity affects millions of Indians on a daily basis, negatively impacts both the agricultural and energy sectors, and puts sustainable economic growth at risk.

To prevent this situation becoming the new normal, urgent and coordinated action to address the supply-demand deficit across sectors is required. Greater efficiency in water use, addressing water allocations amongst sectors, and reducing water loss in supply systems, are critical. Often overlooked, however, is the role of wastewater in achieving these goals.

Today, a whopping 70% of India’s wastewater is released untreated, polluting surface and groundwater sources, and posing a great risk to public health. The policy prescriptions on safe use of wastewater, effluent and sewerage treatment are in place, but better, more effective implementation is needed on the ground. The rapid growth in urban areas across the country makes this ever more urgent, and calls for concerted efforts to address wastewater management in these towns and cities. A mosaic of centralised and decentralised wastewater treatment systems are needed in both urban and rural areas.

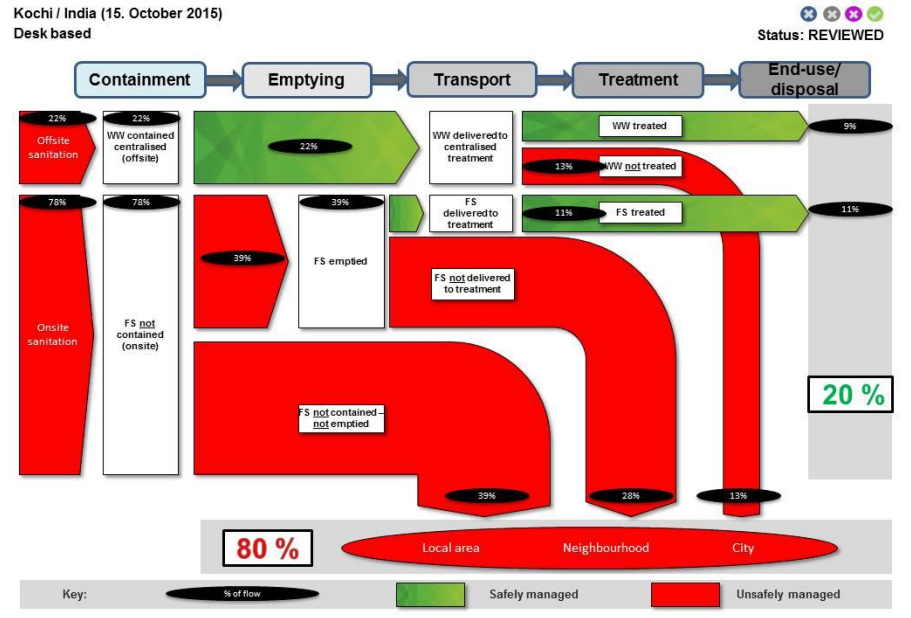

Understanding and visualising the flow of waste within a city is the first step in an effort to plan and manage waste. Shit Flow Diagrams (SFDs), initiated by the Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA), are a powerful visualisation of sanitation in urban centres that can help municipalities, planners, public health officials, and citizens to better advocate for improved sanitation, including addressing wastewater and faecal sludge treatment infrastructure.

A quick analysis of SFDs shows that in many cities, especially in low- and middle-income countries, a large proportion of the population depend on on-site sanitation. Whether or not the facilities are emptied, and whether the emptied contents undergo treatment before reuse or disposal, usually presents the main challenge. This highlights the importance of fecal sludge management (FSM), an issue that is climbing up the political agenda in India, but which scores poorly on indices on access to sanitation in the region.

A quick analysis of SFDs shows that in many cities, especially in low- and middle-income countries, a large proportion of the population depend on on-site sanitation. Whether or not the facilities are emptied, and whether the emptied contents undergo treatment before reuse or disposal, usually presents the main challenge. This highlights the importance of fecal sludge management (FSM), an issue that is climbing up the political agenda in India, but which scores poorly on indices on access to sanitation in the region.

The push to improve sanitation is gathering momentum with the Clean India campaign. As that momentum grows, it is essential that this moves beyond creating infrastructure, or making locations ‘open defecation free’, to also ensuring safe disposal or reuse of the waste generated. The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a health-based risk assessment tool to better plan and manage this across the entire sanitation service chain.

The Sanitation Safety Planning (SSP) is a critical tool that can be used to plan and manage the safe disposal of wastewater, greywater and excreta. Case studies from around the globe demonstrate successful use of the tool in safely managing sanitation by-products. Using the SSP tool, the WHO has actively collaborated with national organisations to promote better planning and management of sanitation in India.

A pilot project in Devanahalli, Karnataka, resulted in the town administration recognising not only the potential of the existing informal reuse of wastewater and faecal sludge, but also the importance of engaging with the stakeholders responsible for its reuse. In addition, through the use of SSP, Devanahalli attracted funding for the construction of a Faecal Sludge Treatment Plant. This, in turn, has attracted attention from both the government and private sector looking to replicate the success.

Attaining total sanitation coverage within urban and rural areas demands robust recycling and reuse of wastewater. This will require multi-disciplinary engagement and processes that empower a variety of stakeholder groups. The larger question of wastewater governance calls for integrated efforts from across sectors, ranging from urban development, public health, engineering, water resources management, pollution control boards, water quality monitoring, and wetland management, to name just a few.

Crucial to addressing the sanitation challenge is recognising and synergising formal and informal knowledge systems. Only then can we hope to capitalise upon the great opportunities wastewater presents for sustainable development.