The world is falling short on implementing the SDGs. This gap leaves an opportunity for leadership on water – leadership that can contribute in multiple sectors because of water’s many connections. By Kala Vairavamoorthy.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have drawn criticism during their negotiation and since their adoption. These criticisms have included that the goals are not legally binding, with countries left to set up their own frameworks for implementation. Many objectives set out in the SDGs are not well defined and are just aspirational. Some see the goals as contradictory – making good noises in the environmental and societal dimensions, but without really tackling the root causes in our economic systems that have created problems in the other two dimensions. Others would argue that political aspects, such as human rights and democracy, are sidelined.

Much of this can be seen as the price to pay for what the SDGs have achieved: the countries of the world agreeing on a development blueprint to guide us for 15 years. Pragmatism is needed for different views and values to coalesce around a common position. The bigger question is whether, having reached agreement, it is backed up with action.

Here we find that no country is on track to meet all 17 goals. Many have failed to take even the basic steps of endorsing the SDGs or mentioning them in their budgets. In its latest progress report, the UN describes the situation, as far as climate and biodiversity are concerned, as ‘alarming’. These facts formed the backdrop to this September’s UN meetings. So there is action, but clearly not enough of it.

Into this space, IWA can contribute leadership, knowledge sharing and technology transfer. Through our five-year Strategic Plan, we believe we can help spark a step-change in progress on many water fronts, across a spectrum that includes utility performance, human capacity, urban development, and innovative approaches that transform current practice.

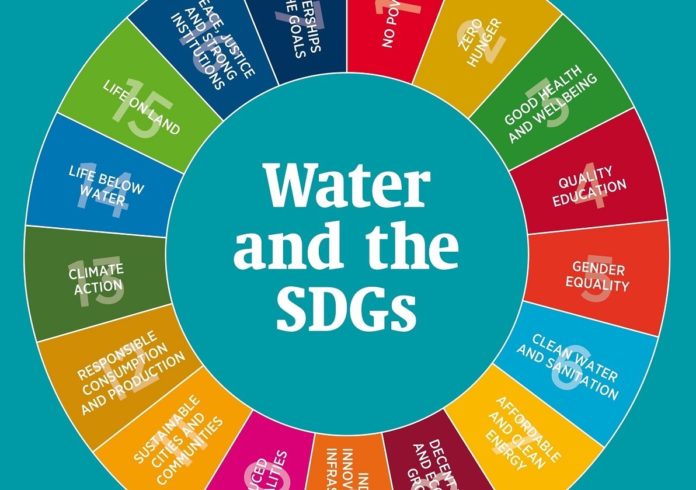

Water’s place in the SDGs

The fundamental point about the SDGs is that they represent a global agenda that has been negotiated and agreed by the countries of the world. They have taken us beyond the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to an agenda that connects developed and developing countries alike, linking North and South. They express a common direction and ambition.

More than this, it is an agenda that has signalled a willingness to take steps beyond those of the MDGs. In the context of water – the focus of SDG 6 – this has meant raising the bar from one that was set at halving the proportion of people lacking access to safe water and adequate sanitation to a goal of universal access to these basic needs. The water component of the MDGs went beyond water and sanitation, but the SDGs have broadened and deepened these ambitions. For example, they specifically articulate aims for wastewater treatment, as well as progressing integrated water management.

Water also has its part to play in the other SDGs; we hear that water is connected to them all. This may be so, and it is a point that does strengthen our message as to the essential value of water, but it should not become a distraction or be overplayed. In the case of some SDGs, the water connection may be on a par with other factors or be overshadowed by other drivers and policy areas.

Nevertheless, water has a crucial role to play in a good number of the SDGs and is an important factor in others. The strength of water’s connections is reflected, for example, in the approach of the sector-defining UN World Water Development Report. This used to give updates every three years, but a switch to annual editions has allowed it to explore key connections – such as with energy and jobs – in depth. This year’s edition highlights water’s role in ensuring the most vulnerable are not left behind in the push to secure the SDGs. Other key links, especially from IWA’s perspective, are those with the SDG goals for sustainable cities and for climate action.

Challenges for SDG progress

Water’s connections to other SDGs reflects the important point that they were not intended as goals to be pursued separately. They should be viewed as a whole, guiding social, economic and environmental development. This means that one of the biggest challenges for countries is to develop and follow integrated policies.

A further criticism of the SDGs is that countries have largely been relabelling what they were doing already, as opposed to really adopting transformative approaches. It may be far-fetched to expect comprehensive, true integration, or even to know exactly what this looks like. But it is certainly vital to break down the siloed approaches that are at the heart of the failure of the development agenda to achieve lasting change thus far.

There are some reasonable explanations as to why progress on this front has not been at the scale needed. One acknowledged by the UN is that the type and scale of change needed has to be rooted in national planning systems.

Even so, the clear message coming from UN progress reports is that much more needs to be done. Indeed, the UN highlights eight systemic and cross-cutting areas where it says fundamental changes are needed. These are: leaving no-one behind; mobilising financing; strengthening institutions for implementing integrated solutions; accelerating implementation locally; building resilience; investing in data; realising benefits of science, technology and innovation for all; and international cooperation.

A practical measure to help drive integration at a national level, and to bring this into national planning processes, is to create a cross-department commission to formalise the integration. Examples of this that receive mention in the latest UN Secretary-General report on the SDGs are those of the Dominican Republic and Jamaica.

Each country will need to address systemic issues in its own way, setting priorities. In the case of the Dominican Republic, it has identified five policy ‘accelerators’ to act as a focus for its efforts. These are: multidimensional poverty reduction; competitiveness and decent employment; sustainable consumption and production; resilient populations; and robust and inclusive institutions.

Water needs and opportunities

SDG progress will therefore depend on cross-sector policies and action. Whether aimed at strengthening institutions, mobilising financing, delivering sustainable consumption and production, or building resilience for populations, national governments need to address issues that span individual sector silos.

This is important for the water sector. It represents the context within which we will continue to tackle water issues. For example, progress mobilising the financing needed to develop and sustain water and sanitation services will be shaped by the wider context of finance and financing in any particular country.

At the same time, national governments will be looking for ways to pursue these cross-sector activities. This is also important for the water sector; it presents an opportunity to demonstrate leadership in the areas where water connects with other issues, and even more generally where integration is the goal.

Lessons and leadership

We in the water sector are increasingly aware of the significance of wider factors on progress with a specific SDG goal – SDG 6. The water SDG points to a need to adopt a systems-based approach. We no longer see resources as being static and isolated, but rather as dynamic forces in constant interaction. From a city perspective, we have our local water supply, waste management and stormwater systems. Each component is inextricably linked within a larger urban system – and that city is itself part of a complex basin in which competing demands for finite water come from many sectors: food, industry, health, energy, transport and the environment. Each of these needs to be connected in the wider system, which is why IWA takes a strategic system-of-systems view.

This awareness underpins, for example, the growing emphasis on taking a systems-based approach to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). Systems thinking tells us that a range of actors must play their part in WASH implementation. That theory then needs to be converted into action – first in creating the frameworks that establish and support the roles of these actors, and then in bringing those roles to life. Progress and experiences of doing this will be shared at the forthcoming IWA Water and Development Congress & Exhibition.

The professional challenge we face in the sector goes beyond this. The need to attend to wider systems means it is important to think more broadly than just technology and engineering solutions. At the same time, we want to foster the innovation that takes technology and engineering forward, and then harness these opportunities within the wider systems.

Non-sewered sanitation is a case in point. We are seeing great progress in terms of treatment and processing technologies, a core strength of our community, and in digital technologies, which change the paradigm by opening up new payment options, for example. Our task is to progress these and, at the same time, progress the wider aspects that will determine whether they succeed in practice. This means looking at social models, such as the role of entrepreneurs in the service delivery – bringing in a jobs dimension – and at aspects such as the use of decision-support systems for option selection (see box).

Similar thinking applies for resource recovery from municipal sewage. The world is waking up to the need to move to a circular economy. Great progress is being made on the technology front, such as in the recovery of phosphate and energy – again, another core strength of our community. But the challenge is as much about how these options work in the real world. Done right, there is the potential for solutions to help rural economies, for example, contributing to other policy goals of governments. This illustrates why next year’s IWA World Water Congress & Exhibition in Copenhagen will feature the SDGs as a central theme.

Both of these examples have a link to jobs, the area explored by the 2016 edition of the World Water Development Report. This reported that 78% of jobs globally are either heavily or moderately water-dependent, with more than one billion people employed in fisheries, agriculture and forestry. There is a 7 to 1 return on provision of adequate water, sanitation and hygiene, and it reported on a study showing that $1bn invested in water supply and sanitation network expansion in Latin America would result directly in 100,000 jobs. So the SDG relevance of water beyond goal 6 is real.

The SDG framework offers an opportunity to better express the wider contribution of water and the water sector, and to provide a frame of reference for how the approaches cultivated by the sector might find use elsewhere. These lessons can also come from building the greater connectivity – between people, institutions and issues – needed to achieve water-wise, climate-resilient cities. Furthermore, these lessons may not just be the usual North to South direction, but South to South – or even South to North – as rapidly developing cities adopt approaches, such as decentralised sanitation, that leapfrog the business-as-usual embedded in the North.

The water agenda

The world is falling short on progress towards the SDGs. However, that means there remains an opportunity to influence the agenda, especially in terms of implementation at the national level. It also means there is a desperate need for references and benchmarks that provide tangible options on how to progress.

There are huge challenges ahead in meeting the specific water goals, and it may seem task enough to provide and progress the policy responses and tangible examples needed to respond to these. But water’s reach into the other SDGs means there is opportunity to contribute to – or provide examples for – the cross-sector or institutional activities that countries need to progress the SDGs as a whole.

Similarly, there is an ongoing need for national policy coherence across sectors and the SDGs. This highlights a need and opportunity to support the individuals and institutions representing water in national platforms, such as commissions, to help them highlight the case for action on water because of its high level of connectivity.

In all of this, there is a clear opportunity for IWA to contribute leadership and practical support in progressing the global water and development agenda.

Dr Kala Vairavamoorthy is CEO of the International Water Association

Sanitation skills and the SDGs

The SDGs provide a very visible reference point for building a response to global needs. This visibility helps open the way for the creation of initiatives and partnerships to deliver progress.

Closing the deficit in sanitation around the world is partly about having the right solutions available – traditional approaches and, increasingly, innovative alternatives to overcome the failings in these traditional approaches. But it is as much about filling a skills gap.

This is the focus of the Global Sanitation Learning Alliance, set up with the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and hosted by IHE Delft. This will promote sanitation skills through a network of partner universities around the world. Alongside this, the Global Sanitation Graduate School aims to train at least 1000 non-sewered sanitation professionals over the next few years – activity that connects, in particular, with the focus of IWA’s Specialist Group on Non-Sewered Sanitation.

These efforts stand to make a substantial contribution on another of the priorities highlighted in the latest UN Secretary-General report on the SDGs: how to realise the benefits of science, technology and innovation for all. As the report notes: ‘Institutional infrastructures at the national level must be supported through access to emerging technology and the skills to deploy it effectively according to the country’s specific circumstances. The inability to do so risks widening inequalities within and across countries.’