The water supply and sanitation aims of the Sustainable Development Goals are vital, but water professionals must look beyond these to the wider need for water security. Jan Hofman, Juliana Marçal and Blanca Antizar set out a vision for a water resilient future.

Water security – sufficient water of adequate quality for all purposes and protection against water-related disasters – is a key requirement for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

For the successful development of global and equitable water security for all, a number of factors are required, including: the development of long-term partnerships between stakeholders; instruments for achieving sustainable financing to ensure projects are viable; innovative approaches to support improved delivery; increased awareness of the challenges and opportunities that impact water security; and an appetite to explore new ways of thinking.

In short, if SDG 6 is to be achieved – ensuring the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation – new vision is required to help the world find pathways to achieving resilient, circular, inclusive, and sustainable water security.

Water security is not just about water supply and sanitation

Water security encompasses various dimensions of policy, such as ensuring access to safe and sufficient water for the health of people and ecosystems, promoting water-based economic growth and food security, and managing water-related risks and uncertainties.

Concepts around water security have emerged and evolved since the 1990s, with contributions around the subject developed by organisations such as the United Nations and other global actors. It is agreed that water security is essential not only to health, but also to poverty reduction, peace and human rights, ecosystems, and education. It is fundamental to the creation of a water-wise society that values water as a precious resource and supports the achievement of the SDGs. Therefore, water security is much more than just providing water and sanitation services, as demonstrated by Jan Hofman, Juliana Marçal and Blanca Antizar in the article ‘How to address water security’, published in The Source in April 2023 (see: https://thesourcemagazine.org/how-to-address-water-security/).

“meeting the SDGs by 2030 should not be seen as a final goal”

Enhancing water security through collaboration and innovation

To ensure water security and meet SDG 6, it is essential that local contexts are prioritised. Identifying needs, resources, challenges, and opportunities locally is crucial. Engaging key actors inclusively allows water management professionals to devise solutions that are resilient, circular, sustainable, and socially responsible, tailored to each community’s needs and concerns.

Cross-collaboration is vital for bridging gaps in financing and policy implementation across different stakeholders, sectors and scales. Flexible frameworks for water security assessment, incorporating interdisciplinary approaches and innovations, are essential. Raising awareness mobilises capital and society, involving local communities in the creation of efficient, responsible solutions. Recently, a diverse panel of stakeholders participated in a workshop organised by two of the authors, Jan Hofman and Blanca Antizar, at the IWA Water and Development Congress & Exhibition (WDCE) in Kigali, Rwanda. The consensus of the workshop was that water security transcends supply and sanitation. Further, it was agreed that meeting the SDGs by 2030 should not be seen as a final goal, but a milestone on the path to sustainable, equitable water management.

The initial step for utilities and stakeholders to achieve water security involves setting operational priorities and integrating innovations. Frameworks such as the World Bank’s ‘Utility of the Future’ programme, the Inter-American Development Bank’s ‘AquaRating’ standard, and Water & Sanitation for the Urban Poor’s (WSUP) ‘Utility Strengthening Framework’ support this task. Their versatility ensures long-term sustainability, addressing challenges such as climate change and the circular economy.

Fast growth and the diversity of the urban environment add to the challenges of reaching high levels of water security in cities. Yet, few studies have so far focused on evaluating the heterogeneous distribution of water security in urban areas, which is a key step in highlighting where inequalities in large cities are present and how best to guide interventions.

A recent study of Campinas, Brazil, published in PLOS Water by Juliana Marçal et al., revealed spatial heterogeneity, emphasising aspects such as vegetation cover and wastewater collection. Despite Campinas’ overall good water security conditions, spatial disparities were found to persist. By quantifying inequalities, inequitable distribution of aspects such as vegetation cover, green social areas, and wastewater collection were revealed. This study pioneered the integration of spatial and inequality analysis, pinpointing areas in need and informing sustainable urban water management, an aspect that is crucial to urban planning and policymaking if sustainable and inclusive urban water management strategies are to be implemented. The study further corroborates that innovation and cross-collaboration, including partnerships with emerging and under-represented stakeholders, are vital for operational improvement and financial scalability.

“we need innovative approaches that are bankable, efficient, appropriate, and responsible”

A vision for water resilient, inclusive, circular cities

To create a forward-looking vision, we must build upon the existing one. A World Bank initiative encourages unconventional water solutions to tackle the water crisis, focusing on water resilience, inclusivity, security, and circular cities. Its comprehensive solutions recognise the interconnectedness of water issues and urban planning.

It is the task of water professionals to empower utilities with innovative frameworks and technologies, enhancing the efficient use of water and building resiliency across sectors. Diversifying water sources will be crucial to the achievement of the SDGs.

Unconventional sources, such as desalination, rainwater harvesting, and renewable energy-driven water reuse, offer weatherproof solutions to bridge the water demand-supply gap. Adopting a circular economy approach addresses climate risks, optimises energy use, and ensures sustainable resource management. Ultimately, this fosters resilient, inclusive water services, benefiting livelihoods, valuing water resources, and engaging local communities.

Unconventional sources, such as desalination, rainwater harvesting, and renewable energy-driven water reuse, offer weatherproof solutions to bridge the water demand-supply gap. Adopting a circular economy approach addresses climate risks, optimises energy use, and ensures sustainable resource management. Ultimately, this fosters resilient, inclusive water services, benefiting livelihoods, valuing water resources, and engaging local communities.

To achieve water security and the SDGs, we need to develop and implement innovative approaches that are bankable, efficient, appropriate, and responsible. These approaches should address the needs already identified by traditional, emerging, and under-represented stakeholders in the water sector. Solutions include:

- Decentralised water supply and sanitation systems that are suitable for different contexts and purposes, such as industrial processes, agriculture, food production, biodiversity and wellbeing;

- Ecosystem innovation that is tailored to a region, fostering the design and execution of bankable projects;

- New and innovative financial instruments that can mobilise public and private funding to improve water security;

- Digitalisation that can provide reliable, up-to-date and accessible data to be used by regulators and stakeholders;

- Utility performance frameworks that can help utilities improve their performance and maturity;

- Capacity building that can enhance the acceptance and adoption of innovation;

- Better governance and accountability that can ensure the sustainability and effectiveness of water security projects.

IWA can play a key role in disseminating knowledge and expertise through its flagship conferences, and by developing and offering tools to the international water community. The World Water Congress & Exhibition 2024, to be held in Toronto in Canada on 11-15 August, will include a water security workshop to further support meeting the SDGs by 2030 and beyond. It is time to start thinking of how to continue and increase cross-collaboration after 2030 – only six years from now. We need new, long term goals; we must strive to keep up to date with the most innovative technologies and approaches; and, above all, we need to keep water security at the top of the global agenda. •

More information

The water security workshop held at IWA’s WDCE in Kigali, Rwanda, was organised by Professors Blanca Antizar and Jan Hofman and included Juliana Marcal, from the University of Bath, Sam Drabble, from WSUP, Marco Aguero, from the World Bank, and Kizito Masinde, from IWA as panel members, and Grundfos Young Water Professionals Dr Sudipti Arora and Anique Azam as rapporteurs.

This article cites a recent peer reviewed paper by Marcal, J.; Shen, J., Antizar-Ladislao, B.; Butler, D.; Hofman, J., (2024) ‘Assessing inequalities in urban water security through geospatial analysis’, PLOS Water 3 (2):e0000213. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pwat.0000213

It presents findings of a study conducted as part of the WISE CDT, funded by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Grant No. EP/L016214/1. Marcal is supported by a research studentship from this CDT.

The authors: Jan Hofman is a professor and Juliana Marcal is a postgraduate research student at the Water Innovation and Research Centre and Water Informatics in Science and Engineering (WISE) Centre for Doctoral Training (CDT) at the University of Bath in the UK.

Blanca Antizar is European director of consultancy at Isle Utilities in the UK and visiting professor at the Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering at University College London in the UK.

The need for cross-collaboration, innovation and awareness

Digest of the Water Security Workshop

Jan Hofman of the University of Bath gave an overview of the UN’s 2013 water security framework, covering economic development, human health, ecosystem health, climate resilience, and peace and security, emphasisng the link to SDGs.

Juliana Marçal, from the University of Bath, researched urban water security assessment, emphasising tailored solutions for diverse city challenges, promoting water accessibility for all residents.

Sam Drabble, from WSUP, focused on improving water utilities’ operations holistically, considering sources, treatment plants, network management, and government involvement. Equity, long-term partnerships, and affordability drive his vision for sustainable urban water services.

Blanca Antizar, from Isle, highlighted innovation’s importance, addressing social integration and service delivery challenges, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Her vision includes circular economy models and water-efficient data centres in an AI era.

Marco Agüero, from the World Bank, outlined a roadmap for water security, emphasising financial solutions, private sector involvement, and resource mobilisation. His holistic approach aims to address the investment gap and enhance global water availability.

Kizito Masinde, from IWA, advocated a new paradigm, emphasising productive water use, addressing climate change, air pollution, and resource pressures. He underscores water reuse, energy-water connections, and holistic management.

Sustainable Development Goal 6: meeting 2030 targets and beyond

According to the UN, in 2022: 2.2 billion people still lacked safely managed drinking water, including 703 million without a basic water service; 3.5 billion people lacked safely managed sanitation, including 1.5 billion without basic sanitation services; and 2 billion lacked a basic handwashing facility, including 653 million with no handwashing facility at all.

Having a close look at the UN progress chart 2023, which uses trend data between the baseline year of 2015 and the most recent year, it reveals significant and concerning challenges. The progress assessment of Goal 6 indicates that 6.1 safe drinking water, 6.2 access to sanitation and hygiene, 6.4 water use efficiency, 6.5 transboundary water cooperation, and 6.b participatory water and sanitation management are moderately or severely off track; while on 6.3 water quality, 6.6 water-related ecosystems and 6.a international cooperation on water and sanitation there is stagnation or regression. To meet 2030 targets, the pace of progress will have to accelerate: six times in drinking water, five times for sanitation, and three times for hygiene. Integrated water resources management implementation also needs acceleration.

Key strategies set by the United Nations to get Goal 6 back on track include increasing sector-wide investment and capacity-building, promoting innovation and evidence-based action, enhancing cross-sectoral coordination and cooperation among all stakeholders, and adopting a more integrated and holistic approach to water management.

Adapted from The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition

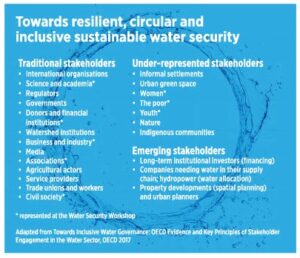

Towards resilient, circular and inclusive sustainable water security

Traditional stakeholders

- International organisations

- Science and academia*

- Regulators

- Governments

- Donors and financial institutions*

- Watershed institutions

- Business and industry*

- Media

- Associations*

- Agricultural actors

- Service providers

- Trade unions and workers

- Civil society*

Under-represented stakeholders

- Informal settlements

- Urban green space

- Women*

- The poor*

- Youth*

- Nature

- Indigenous communities

Emerging stakeholders

- Long-term institutional investors (financing)

- Companies needing water in their supply chain; hydropower (water allocation)

- Property developments (spatial planning) and urban planners

* represented at the Water Security Workshop

Adapted from Towards Inclusive Water Governance: OECD Evidence and Key Principles of Stakeholder Engagement in the Water Sector, OECD 2017